Julia Weist

works exhibitions news about

nada new york

Booth 4.08

May 2 - 5, 2024

about

Julia Weist never expected to become a private investigator. Compared to the cops, fire marshals, and insurance fraud analysts who are normally granted this powerful license, her primary qualification was a 2019 public art contract with the City of New York that embedded her in the Department of Records and Information Services. It was hard to imagine that the bureaucrat reviewing her application would see this period of artistic research as “investigative experience” or the resulting photographic prints—layering city records about the arts with the retrieval slips used to obtain them—as “evidence.” More likely Weist would follow the path of other denied applicants: she would appeal the decision and proceed to adjudication, when a judge would determine how her practice failed to qualify her for the job.

Weist spent several months preparing for this outcome. Her artwork would literally be put on trial, and the record of the proceeding could serve as raw material for a future project. The New York Department of State had other plans for the artist—it approved her application.

Our popular idea of the private investigator comes from film noir: the silhouette on frosted glass, the demons and drink, the cigarette forever on its last drag. This character is often an amateur and almost always a lone agent, nimbler but less resourced than law enforcement. His clients are impatient, and the money is usually good, so any means are the right means to obtain what they’re seeking.

Much like its depiction of the art world, Hollywood hasn’t exactly striven for accuracy. As Weist came to learn firsthand, licensed private investigators cannot operate with impunity, though provided they follow protocol, have extensive access to sensitive and private information. This is the departure point for her current body of work—including three series of photographic prints at NADA—which the artist made using the databases now at her disposal. In adherence to the letter but not the spirit of the law, she has cast the gaze of the private investigator beyond its usual targets, finding instances of comedy and beauty in public space that seem to stare back at their surveillant.

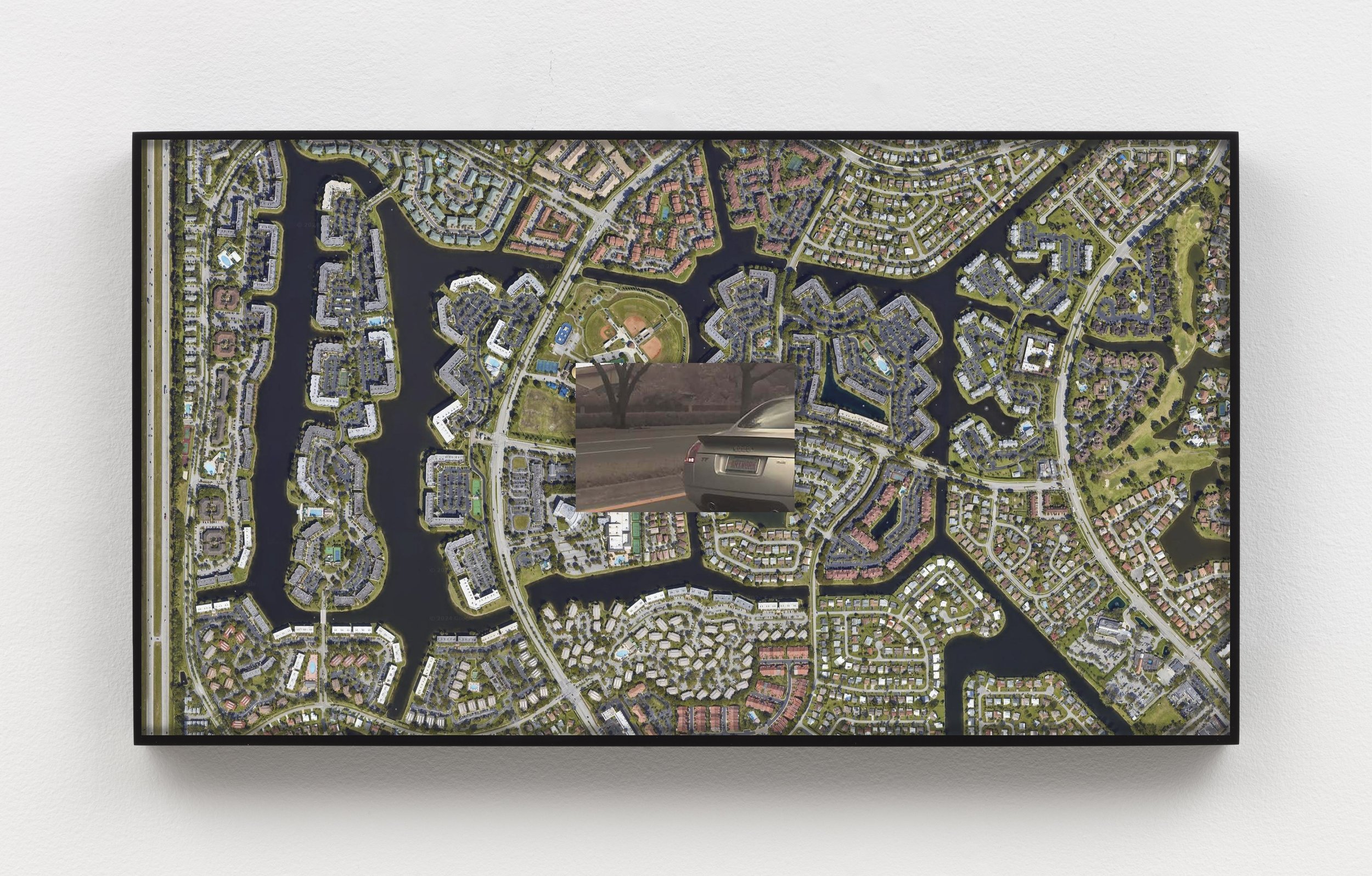

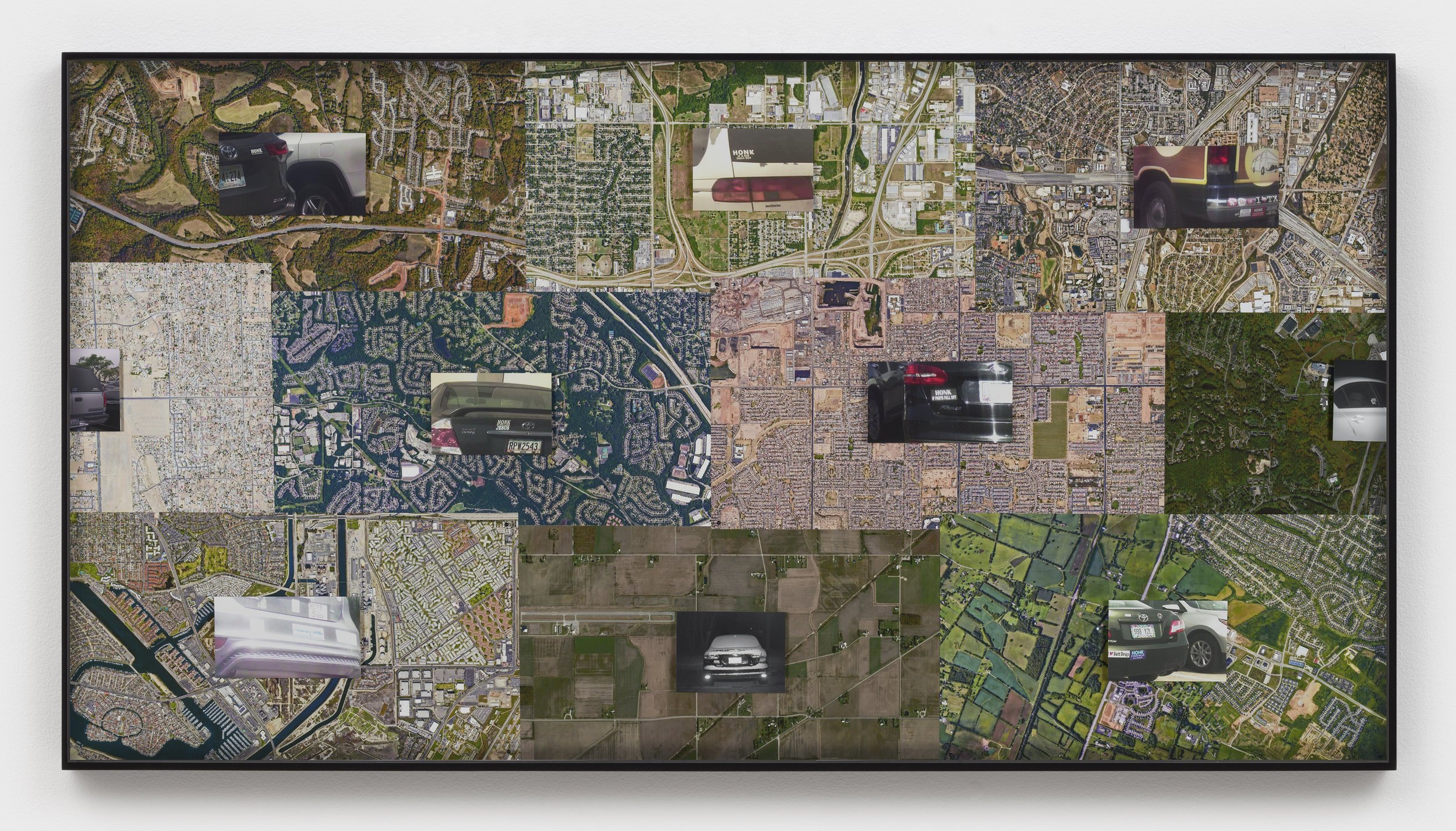

For her presentation at NADA, Weist exploits a loophole in the system, sourcing visual content through a vehicle location database without needing to provide a legally permissible purpose for each search. Because license plates are visible in public space, private investigators ostensibly have the same access as anyone else—even if the database affords the exceptional ability to track their locations over the past 36 months without having to shadow cars in person. In one series, Weist looks for motifs across these images, often found on bumper stickers professing the politics and sensibilities of drivers. Some soliciting a “Honk”—“if you love Jesus,” “if Helen Keller is a fraud,” “if you do everything people tell you to do,” etc.—variously seek community on the road and play with the power dynamics of seer and seen. Others show how a single word can span social and political spectrums: “Proud to Hire American,” “Proud Veteran,” “Proud Ally.” When possible, Weist omits drivers’ plates to protect their anonymity. At the same time, she layers the images over satellite photographs of the sites where they were taken, amplifying the dread lurking beneath even the funniest of them. So many details of our lives have been documented without our knowledge, can be privately accessed, and may become part of a story being written about us. Weist’s pieces give us the vantage point of the private investigator, but their effect is to make us realize just how vulnerable we are to capture.

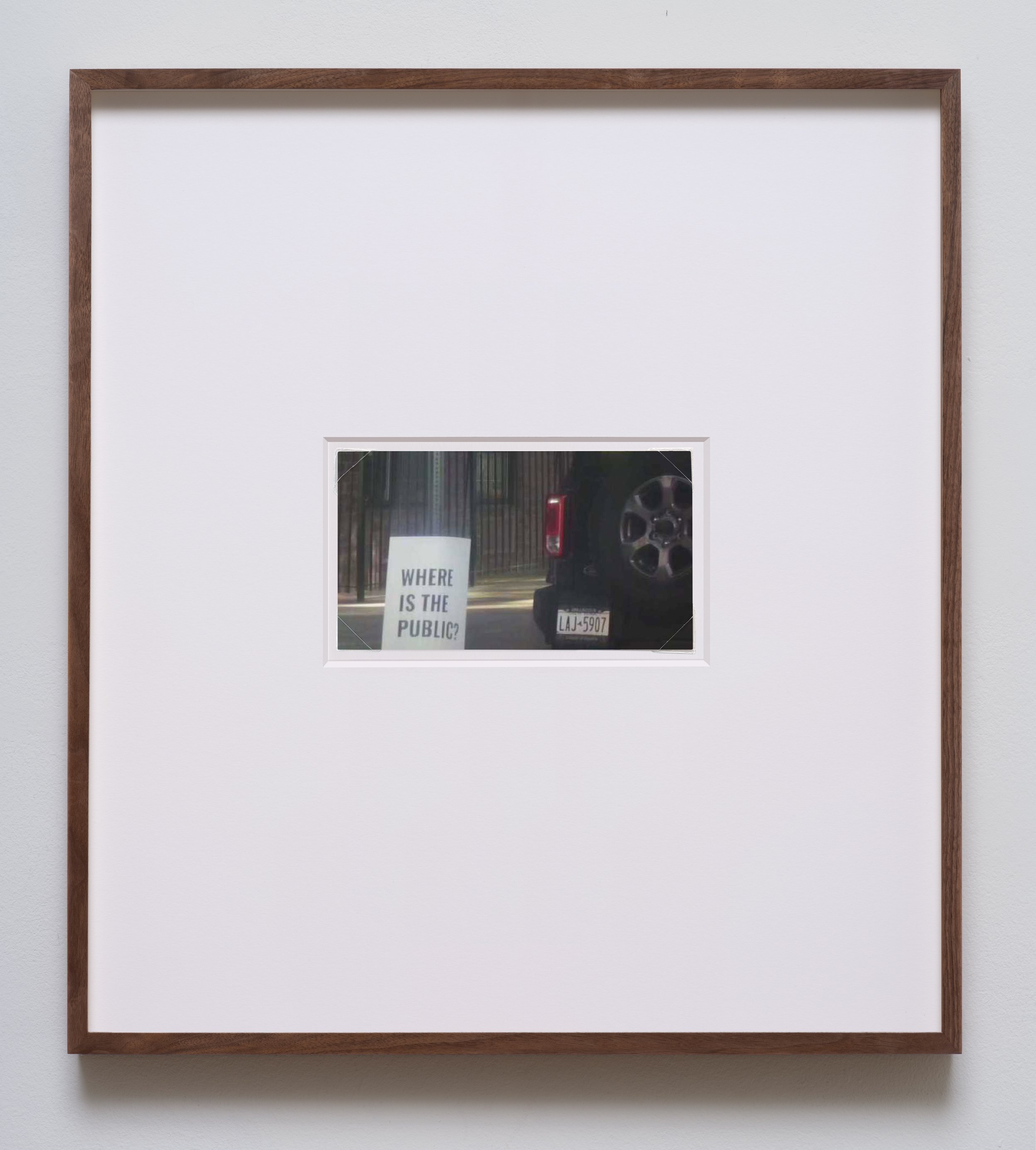

Vehicle Sightings, another series on view, works with the same database, which is populated by images shot by tow trucks in search of cars to repossess. Though taking photographs isn’t necessary for this process, as a scan of a license plate will trigger an alert, there’s money to be made in generating photographic ‘proof’ that vehicles have been at specific locations. Seeking to intervene in this visual economy, the artist parked her and friends’ cars near the entrances of repo yards to increase the chance they’d be seen, then searched for their plates on the database to obtain the images on view. What results is true PI cinema, filmed by unwitting repo men and performed by vehicles Weist embellished with flowers, an oversize tutu, and Holbein’s anamorphic skull, which the camera is unable to see from an undistorted angle. A sign beside one car asks “Where is the Public?” Has the public sphere shrunk to an encounter with a probing eye? To make the companion series Watching the Watcher, Weist ran the plates of the tow trucks themselves, discovering images of trucks accidentally shot by others. Taking a postmodern turn, this particular surveillance network—independent of her direction—happens to play itself.

Weist, sunburned after hours of waiting for her closeup, sits on the curb in one image from Vehicle Sightings. She stares the camera down while also meeting our gaze, acknowledging that she too is caught by the system which gives her considerable power over others. Julia Weist the artist and Julia Weist the private investigator, the person who poses in this image and the one who finds it through the database: the gap can seem infrathin, yet it holds a force that entangles us all.

Text by Tyler Coburn

Julia Weist is a visual artist based in New York. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Guggenheim Museum, Brooklyn Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Jewish Museum among other collections. She has recently exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, Art Institute of Chicago, Queens Museum and The Shed and internationally at the Hong-Gah Museum, Taiwan; nGbK, Berlin; Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam and the Gwangju Biennale. Her most recent solo exhibition was at Rachel Uffner Gallery and her latest public artwork, Campaign, debuted in Times Square in 2022. She will present her first solo exhibition with the gallery Moskowitz Bayse in September 2024.