Ernesto Renda

works exhibitions news about

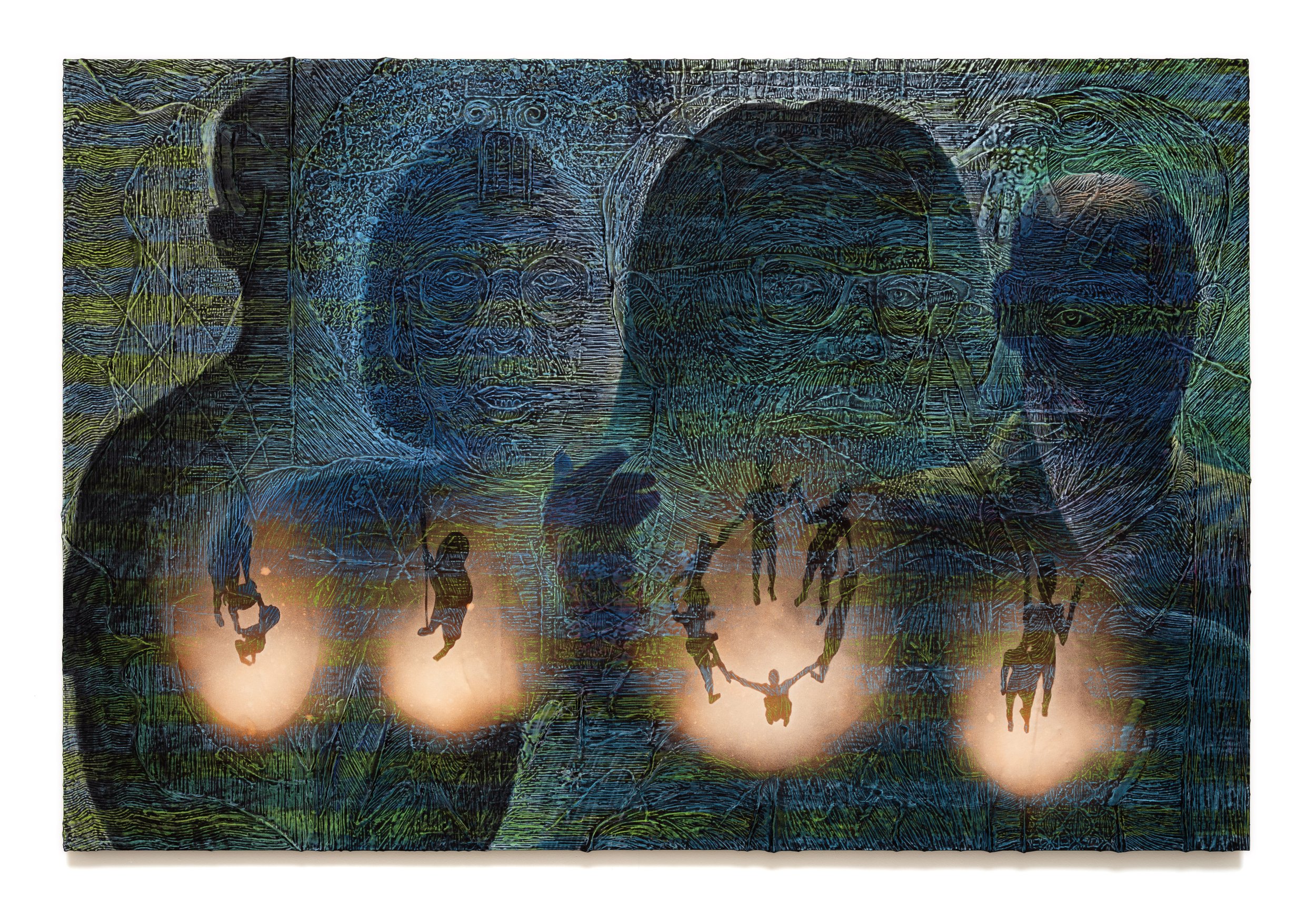

the moment of truth

March 30 - May 11, 2024

Opening Reception | March 30, 6-9pm

exhibition text

And still the light

fills wind-tossed branches,

makes clouds iridescent

islands in the sky. And still

the same light (for nothing

in nature is private)

insists on a shadow in the road.

–Claudia Rankine, Nothing in Nature is Private (1994)

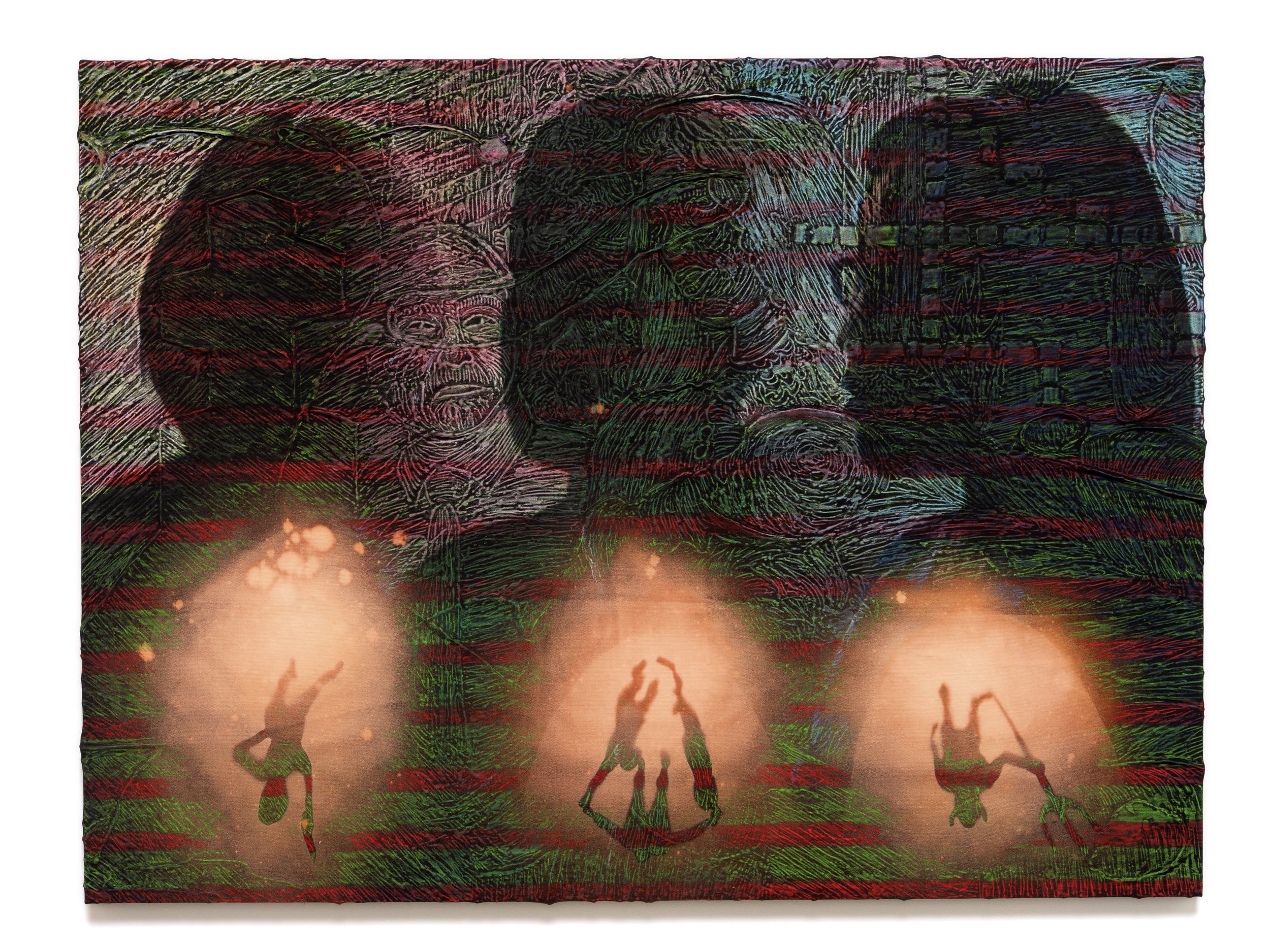

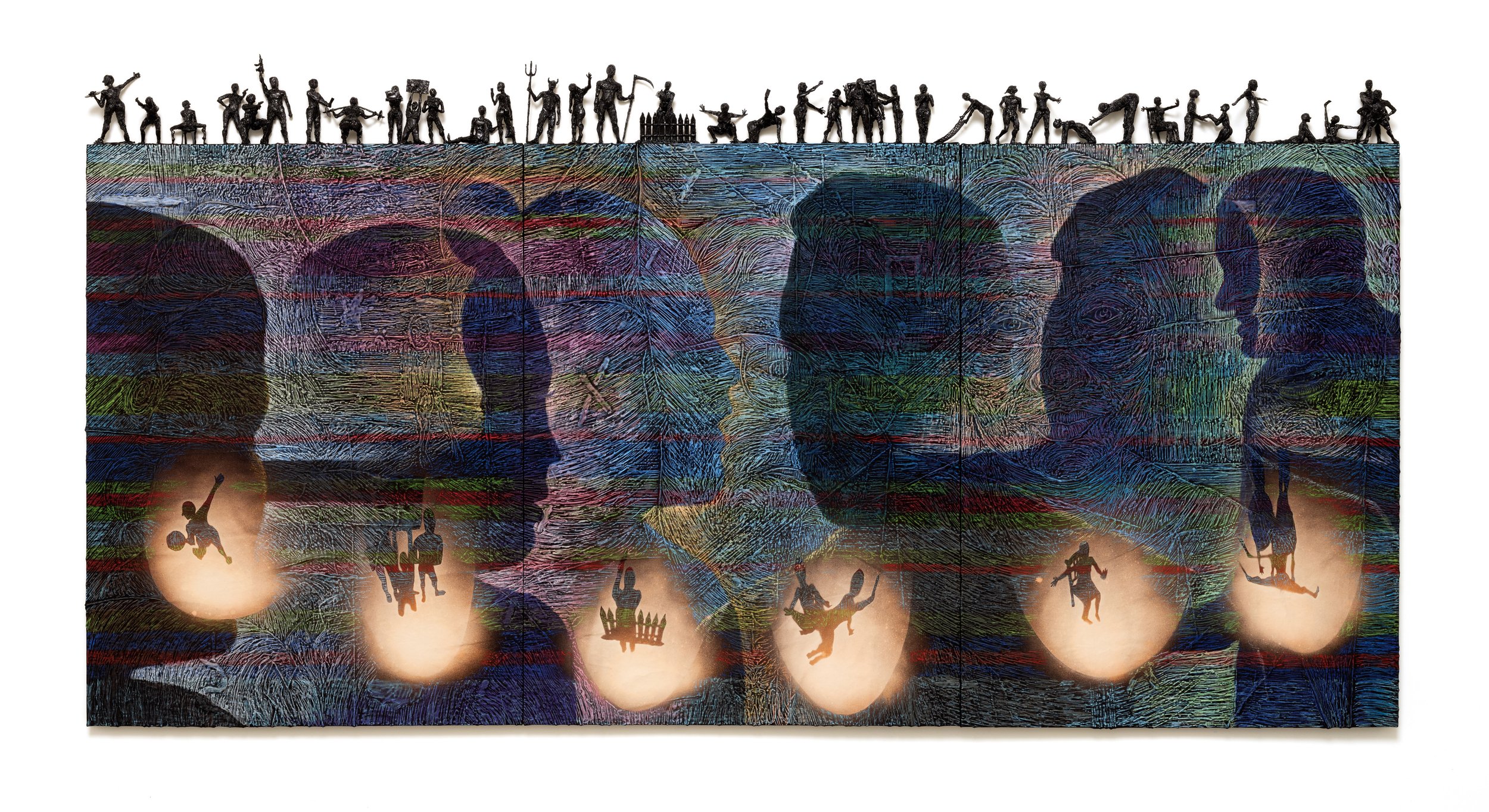

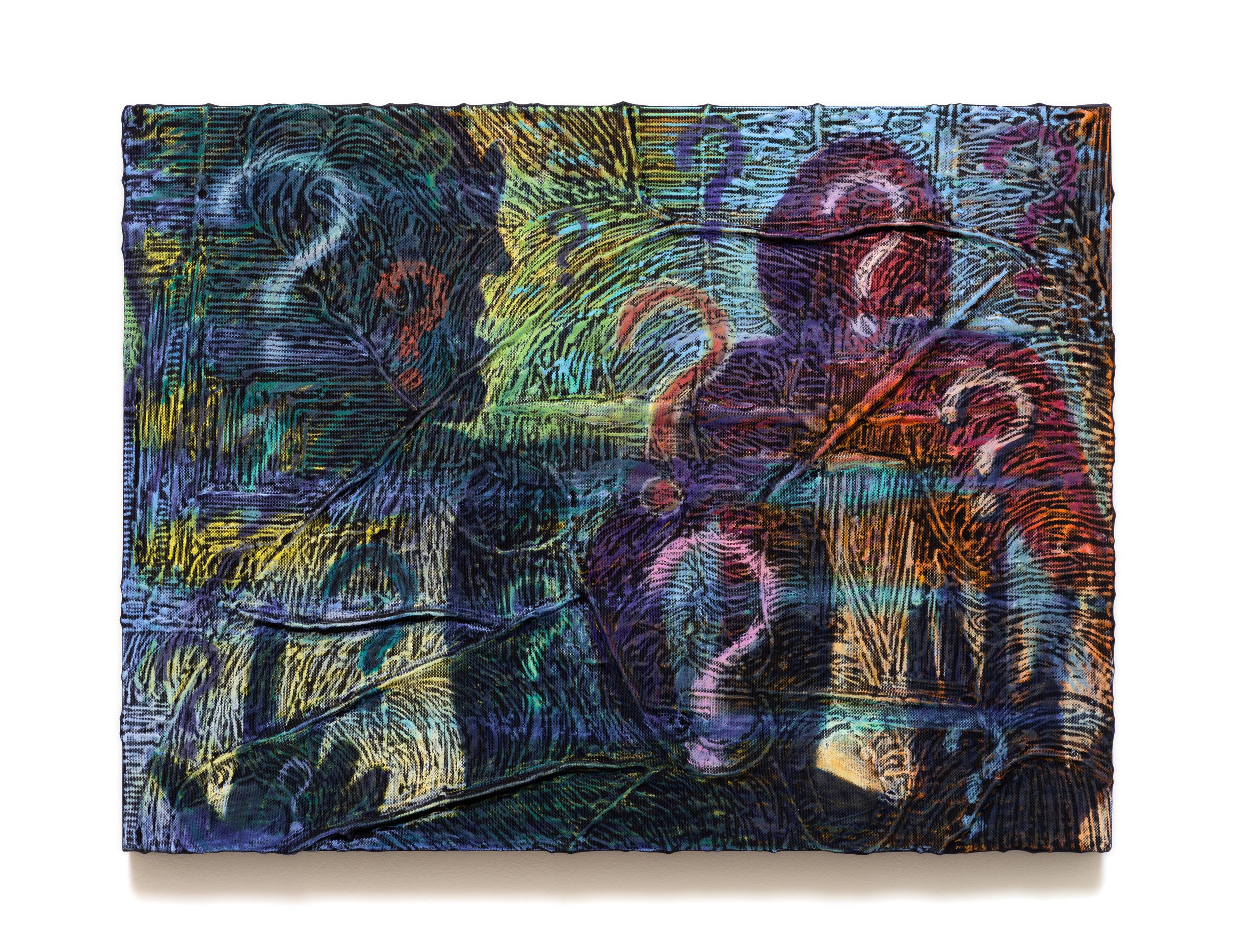

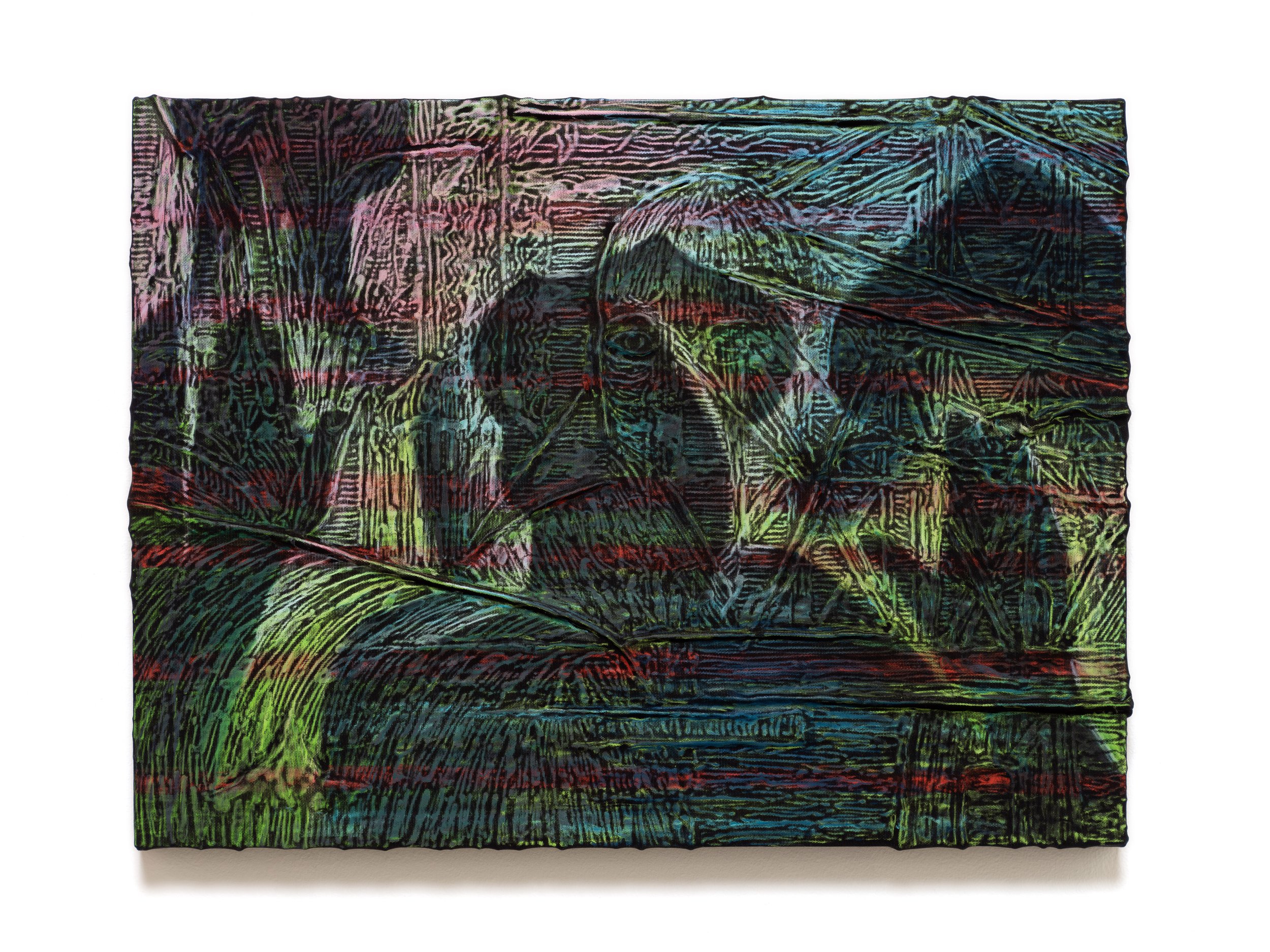

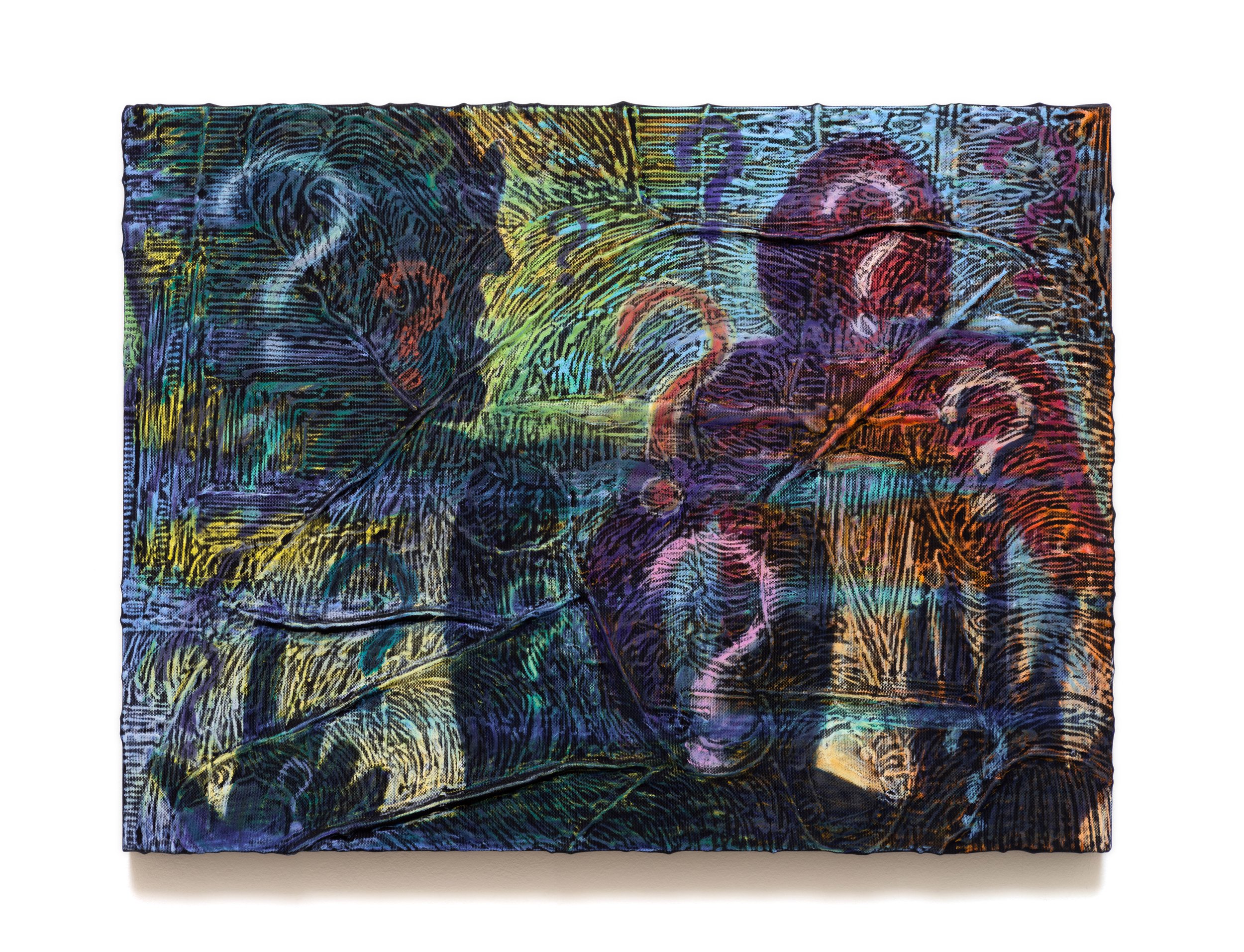

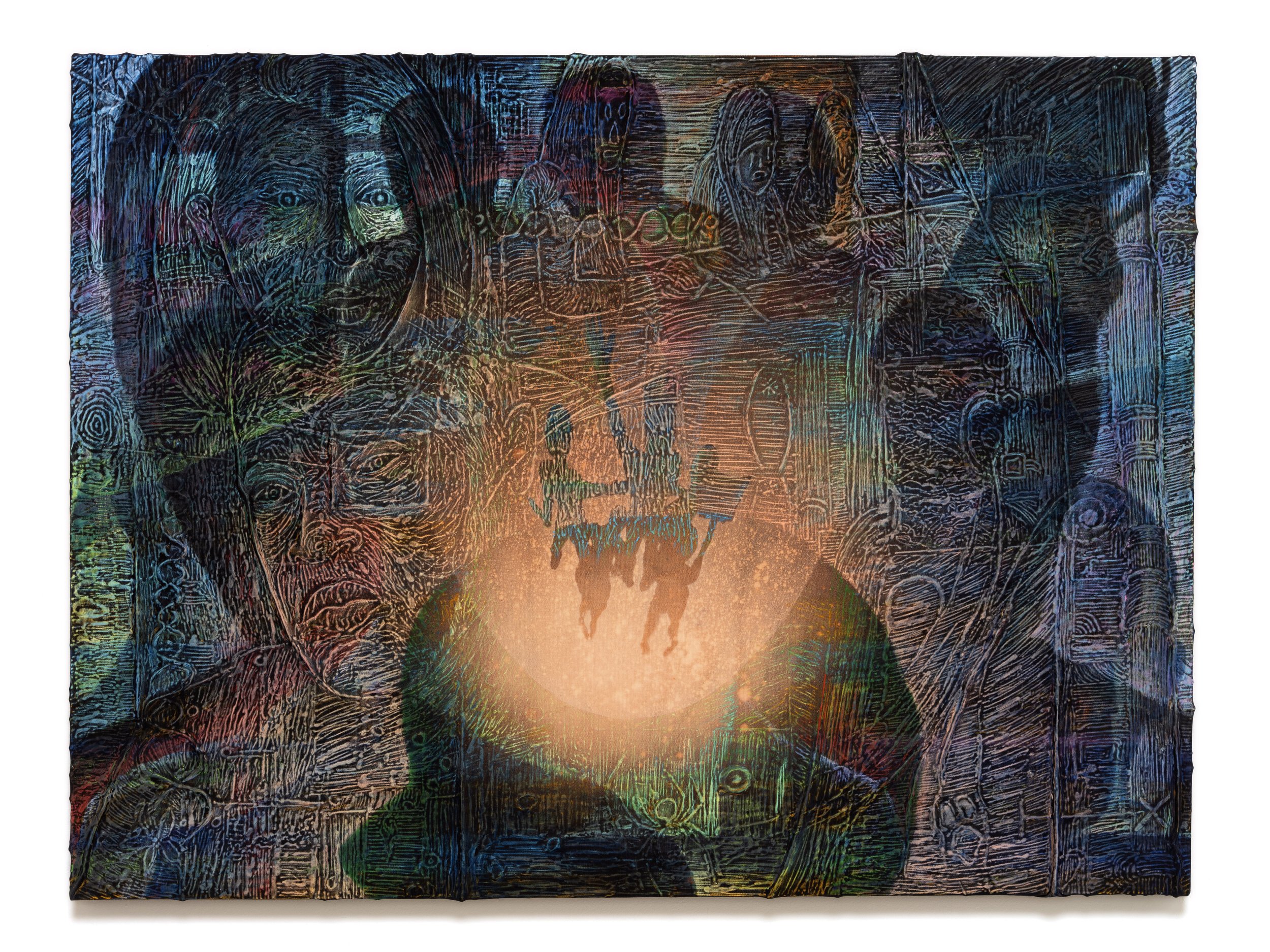

Ernesto Renda’s paintings are hard to look at. There’s nowhere for the eye to rest, no break from the staccato flashes of polychromatic pastel on dyed black unprimed canvas. Their extreme contrast has a strobe-like effect, demanding constant retinal movement, somehow achieving the analog kitsch of rainbow scratch paper. It’s irresistibly lenticular, like staring for too long at the metal grooves of moving escalator steps. The details are too much. Fluorescent pastel line drawings of faces with vacant expressions are intersected by darker, photo-negative horizontal filaments that suggest VHS tracking lines, or the spectral glare of sunlight on a computer screen. Profiles of shadowy backlit figures are overlaid onto them, referring to the anonymized confidential sources of television news specials and investigative documentaries. These people don’t want to be seen, so Renda has made them hard to look at. It conjures a state of overwhelm, like many of the artist’s reference clips do: footage of pseudonymous, faceless sources telling their stories of abuse, violence, shame, fear, despair—all using the familiar TV-producer trope of backlighting and voice distortion. Their target audience is seeking overwhelm—a greed for the traumatic—the kind that predicates an economy of hate-clicks and “trauma porn.”

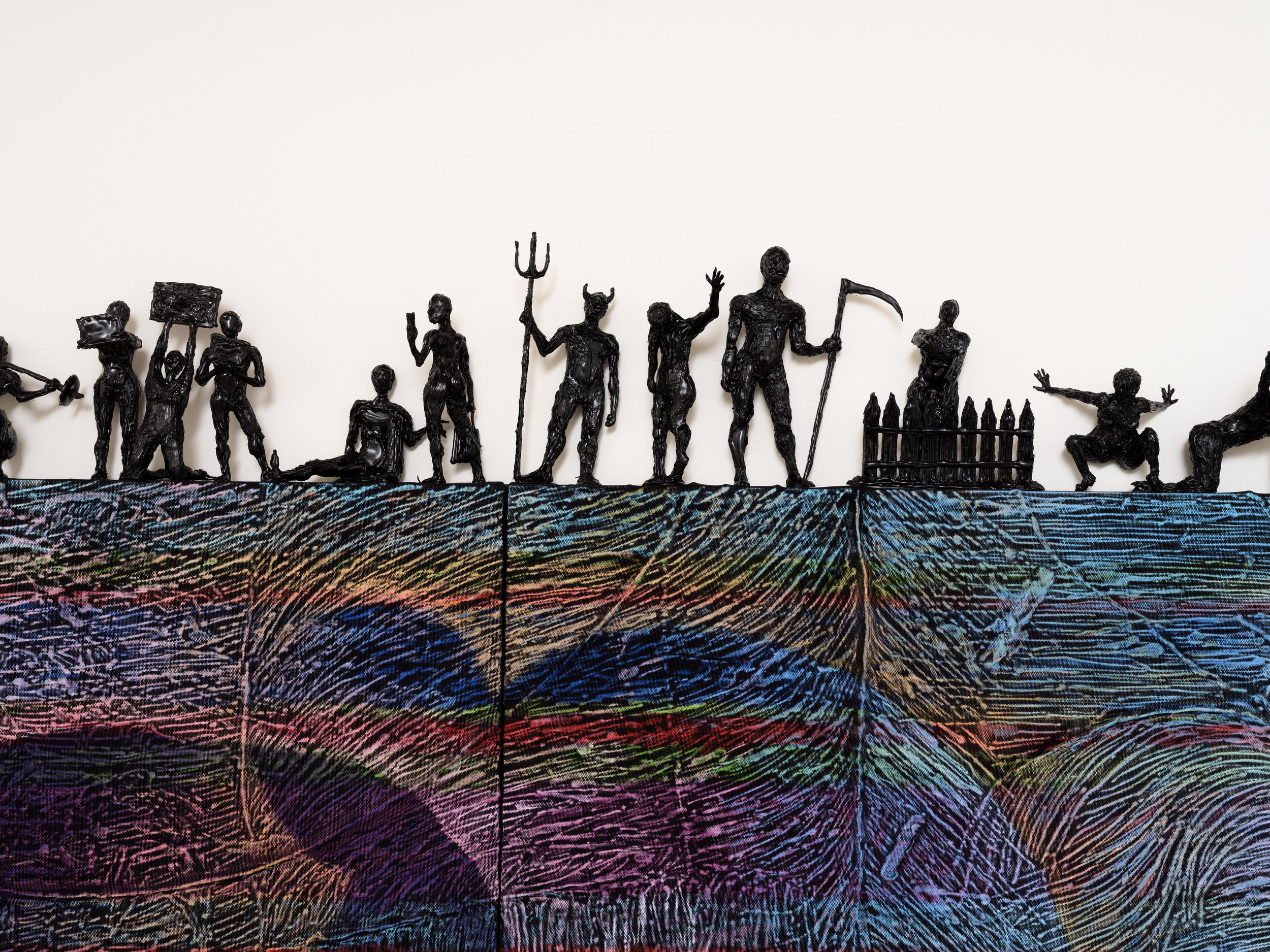

Over these shadowy figures, and seemingly above the fray, are several spotlighted exhibitionists—play-actors seeking recognition for their mundane achievements of dancing, weightlifting, gardening, et cetera. Renda has sculpted them out of black-pigmented hot glue and given them a trompe-l’œil spotlight and shadow with bleach. Their stark contrast demands attention. These characters are the playful antidote to, and distraction from, the sullen figures beneath them: they want to be seen. Instead of anxious secrecy, their implied viral videos might start with eager declarations of “STORY TIME!”

Each meticulous layer of Renda’s relief paintings—figural line drawings, backlit profiles, VHS tracking lines, flares of light—represents a different “allegory of mediation.” His unique relief effect derives from a raised hot glue underdrawing on panel, which is then wrapped in black canvas. Mimicking the diachronic aspect of film, Renda’s dual surface preparation and frottage situate their impact between multiple shots rather than a single still frame. The initial image encountered, drawn on the surface in pastel (what Renda calls the “overimage”), is mediated by the linear relief image revealed through rubbing (the “underimage”). Contrary to the smooth, flat nature of the screen, Renda introduces a busy surface to better represent the visual density of the motion picture experience—what Raymond Williams described in the 1970s while watching the broadcast of a film on American television: endless advertisements and previews of other programs interrupted the film and psychically cast its actors in the plot of the commercials, creating “a single irresponsible flow of images and feelings.” Renda’s informational maximalism is equally irresponsible to the feelings of his viewers. But he prefers to show, not tell, because, as he points out, the schizophrenic conventions of the internet are too obvious to trivialize, “and too cringe to complain about.”

Renda’s focus on the anti-subject of confidential sources emerged from his ongoing interest in news media’s apprehension of the queer subject. This body of work began to take shape following his encounter with “The Homosexuals,” a landmark 1967 episode of CBS Reports, notable for being one of the earliest televised discussions on homosexuality in the US: a still from the episode can be seen on the far left of MSM (all works 2024). Renda started to collect anonymous interviews from all manner of TV, documentary, and YouTube media. In some clips he discovered, a paid actor would sit in for the confidential source, or an editor would splice in stock videos to avoid visualizing the source altogether. As a result, he became increasingly “infected with doubt” about the melodramatic trope of backlit anonymity. This cynicism ultimately reached its pinnacle in WHISTLEBLOWERS and GALLERY ASSISTANTS, two works that reflect a demiurgic shift in their exclusive use of stills from stock footage and AI-generated imagery prompted with tags like “backlit confidential source.” Renda’s painted subjects thwart television’s confessional science with their campy anonymity: their stories are unimpeachable, because there is nobody to impeach.

Following the example of the psychoanalyst and the TV producer, Renda fetishizes the unsaid. He distinguishes between the overt, unspoken, and ideological intentions of each interview he references. He recognizes his viewers as televisual subjects prone to media skepticism, and therefore locates his interest in “truth-making.” The animating problematic in this body of work is the anonymity paradox: confidential sources are both secret and spectacle. Renda probes anonymity’s discursive character, as both a political instrument and an aesthetic subversion. It’s a foil to the carnival sense of the world we’ve developed from the informatics networks we occupy. It’s the relativity of order—and the ambivalent ritual—that Mikhail Bakhtin, scholar of the carnivalesque, enumerated the pleasures and pains of. He wrote that the mask—the oldest technology of anonymity—is “connected with the joy of change and reincarnation, with gay relativity and merry negation of uniformity and similarity;” that it even “rejects conformity to oneself.” But the mask is inconsistent with cinema’s “will-to-see,” says Renda.

Unlike Renda’s anonymized subjects, most ordinary people can’t make recourse to the confidential. Privacy is not evenly dispersed across an undifferentiated public. A claim to the right to privacy is not even fathomable for certain disenfranchised groups. It is a racialized and nationalized construct, as per Jasbir Puar, whose Terrorist Assemblages (2007) is among Renda’s primary influences. This contouring of public and private, a distinction Renda problematizes, is pursuant to bourgeois law, and fraught with contradiction. Anonymity is increasingly conscribed by the surveillant assemblages of connectionist capitalism—via data mining, information brokerage, and so on. Privacy is the unlikely fantasy of a public that has naturalized its own constant, compulsory visibility. “Nothing in nature is private,” as Claudia Rankine once suggested.

Confidential sources recognize the problem of the complaint, à la Sara Ahmed: that when you point to the problem, you become the problem. Not all Renda’s sources are noble: some of them are the problem, and mean to reject their own moral culpability. He presents a sudden, surprising vicinity of heroes with perverts, whistleblowers with reactionaries—all siloed according to each distinct category, but displayed in tandem. As Renda indicates, backlighting and audio distortion emphasize the danger and the consequences of speaking “the truth.” Television’s visual coding of anonymity is both nondescript and fittingly high contrast for high drama: its dramatic contrasts of light and dark create a narrative chiaroscuro that often trends toward the facile. Some confidential sources respectably assert their freedom of speech and that of the press—but others are opportunists, hoping for freedom from consequences.

Text by Amelia Farley