Sculpture Into Photography

Matthew Brandt

Brian Bress

Rachael Browning

Valerie Green

Joey Frank

Gregory Kalliche

Anthony Lepore

Robert Heinecken

Barbara Kasten

Soo Kim

Antonia Kuo

Adam Moskowitz

Matt Lipps

Christopher Richmond

Letha Wilson

July 15 - August 19, 2023

Critics were baffled by the Museum of Modern Art’s 1970 exhibition Photography into Sculpture. Walking into the gallery, reviewers who knew MoMA’s photography department for 8x10 silver gelatin black-and-white art prints with a documentary tinge instead found a “photography” show made up of “[C]ontour vacuum-molded plastic containers for photographs and film transparencies; film positives layered in lucite constructions of varying depths, which are seen by reflected or transmitted light; photosensitized contour-molded cloth sculptures; life-size figurative compositions constructed from several hundred glass transparencies with multi-dimensional views; fabricated pictorial or illusionistic boxed environments; participation puzzles; topographic landscapes which are contoured by a vacuum process; lucite cubes of photographs; three-dimensional wall constructions; reductive, or minimal, sculptures of multiple pictorial boxes; and light/ negative constructions.”^1

Whatever these objects were, they were not photographs of value, wrote an irritated Hilton Kramer, then the chief art critic at the New York Times. They were gimmicks, "facile tricks and vulgar distortions,"^2 which “violate[d] the integrity of the photographic process.”^3

But violation–or exploration–was the show’s intent. Curated by Peter Bunnell, it featured twenty-three young artists who embraced new industrial materials and alternative printing processes to expand the limits of what photography could be, focusing on photographic form rather than the medium’s ability to convey narrative. These artists experimented with form more than content, encapsulating a sentiment hailed by Los Angeles-based photographer and educator Robert Heinecken that a photograph is " not a picture of, but an object about something."^4 Bunnell wanted to expand photography's scope beyond the traditional 'flat' print, he wrote, to "engender a heightened realization that art in photography has to do with interpretation and craftsmanship rather than mere record-making." He sought to expand the terms in which a photograph could be art, breaking down its documentary silo and putting it in conversation with other forms.

Bunnell's exhibition has had a robust afterlife, as has the prevalence of photo sculpture in contemporary art, which seems to emerge in some permutation or another with each generation. Throughout the 2000s, several major exhibitions showcased "photo-sculptural practices,"^5 and in 2011, the Los Angeles gallery Cherry and Martin presented a restaging of Bunnell’s show, renewing interest in the historical artists on the 1970 exhibition's roster. In the 50 years since Photography into Sculpture, camera and printing technology have evolved and photography has grown more established as an art form. But artists continue to interrogate photography’s materiality, its relationship to illusion, and its possibilities beyond the realms of 2D.

Moskowitz Bayse's Sculpture Into Photography takes the title and premise of Bunnell's exhibition and reinterprets its thesis for an age in which our everyday experience of photography is both less material and more ubiquitous than ever before. Taking Robert Heinecken’s work as a historic point of departure, the exhibition features fifteen artists with work primarily from the past ten years, and proposes a similar investment and interest in pressing against boundaries of traditional photography via experimentation with materiality and technology. But whereas the original 1970 cadre of artists responded to the prevalence of minimalism and pop art and the ubiquity of traditional fine art silver gelatin photography, the current group's focus is experimenting with verisimilitude and a desire to transform a photograph from a reproducible medium into a unique or singular object. Works present physically on a spectrum of dimensions, but posit a central question: where does the photograph end and the object begin, and vice versa?

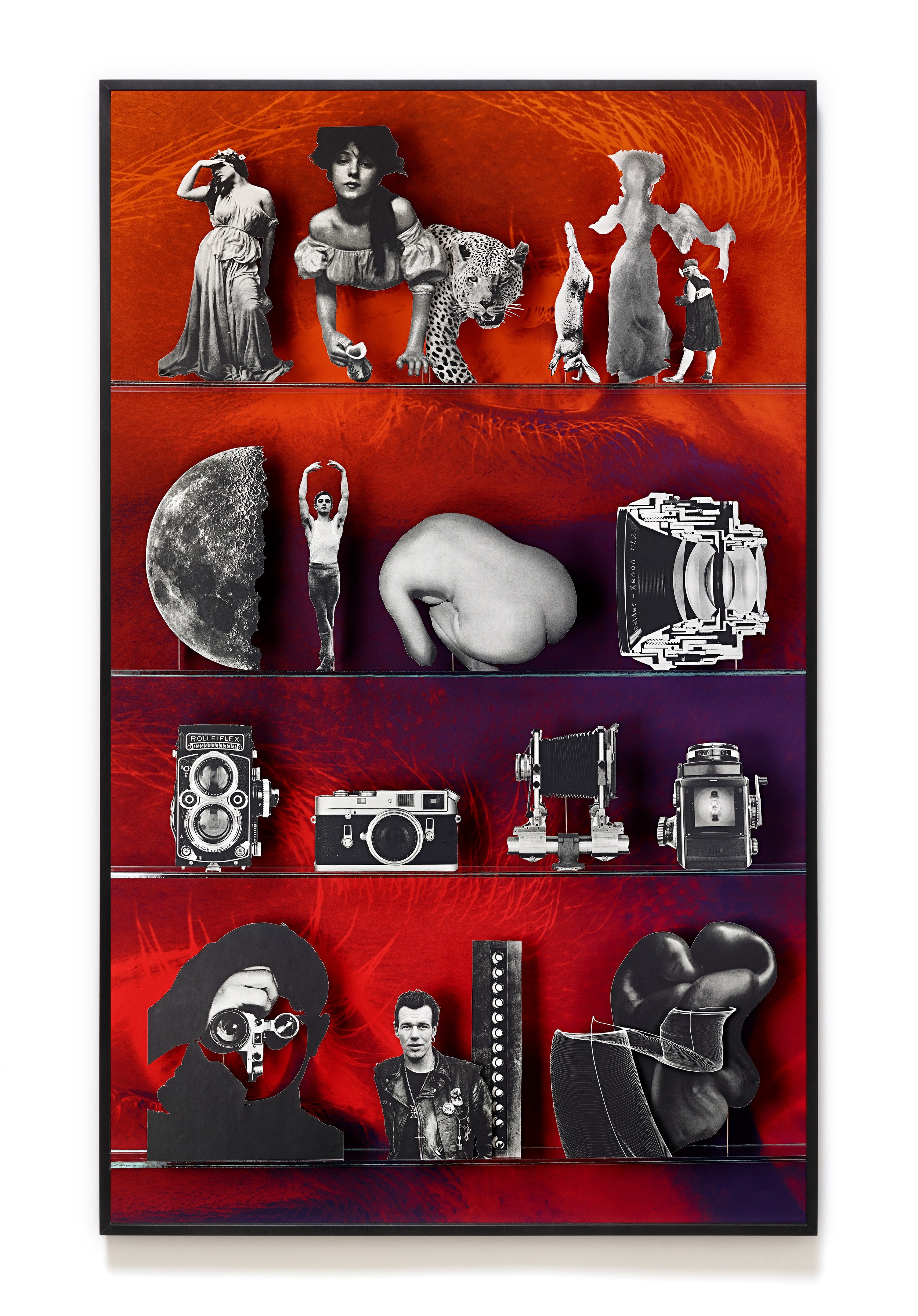

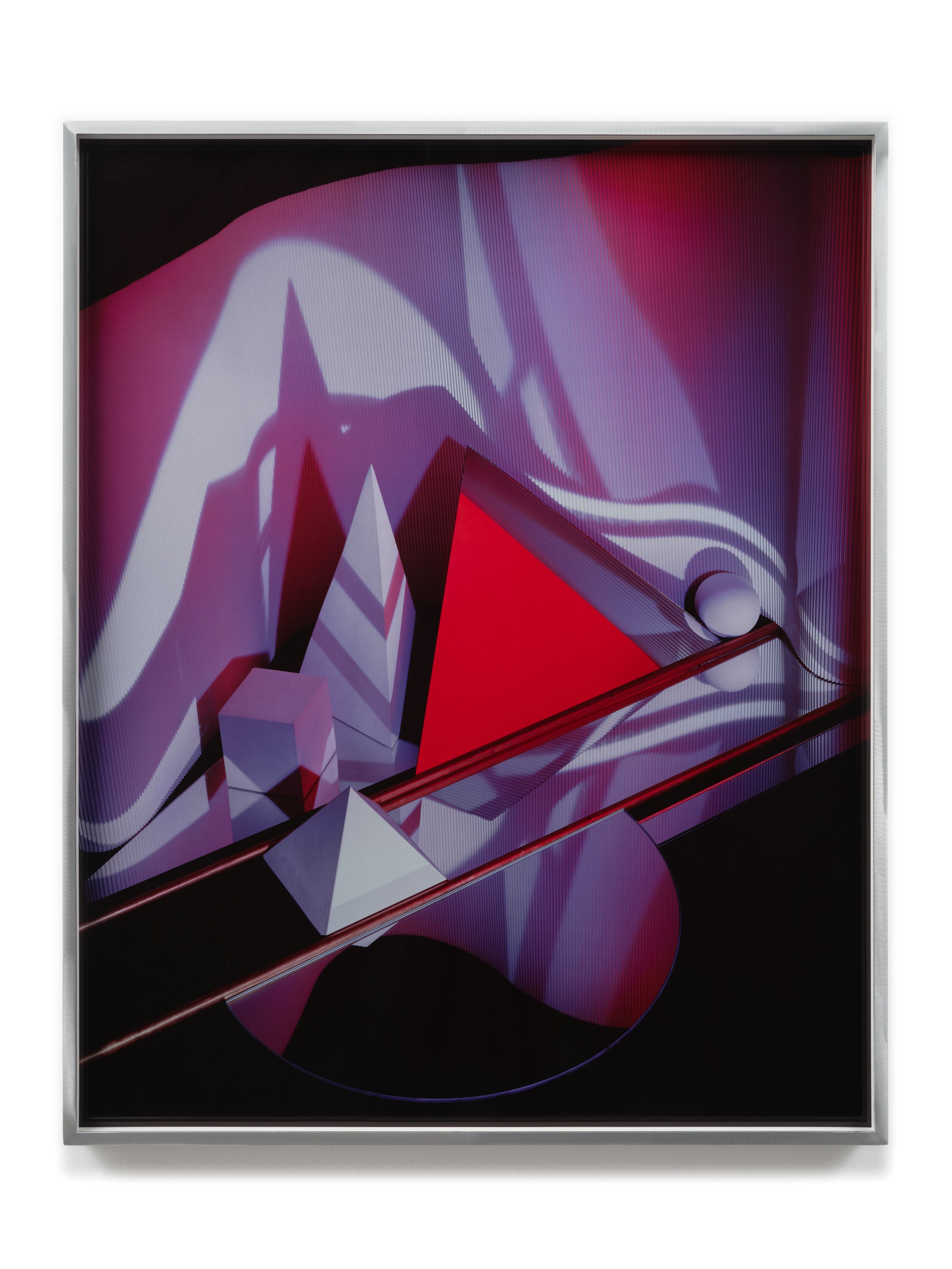

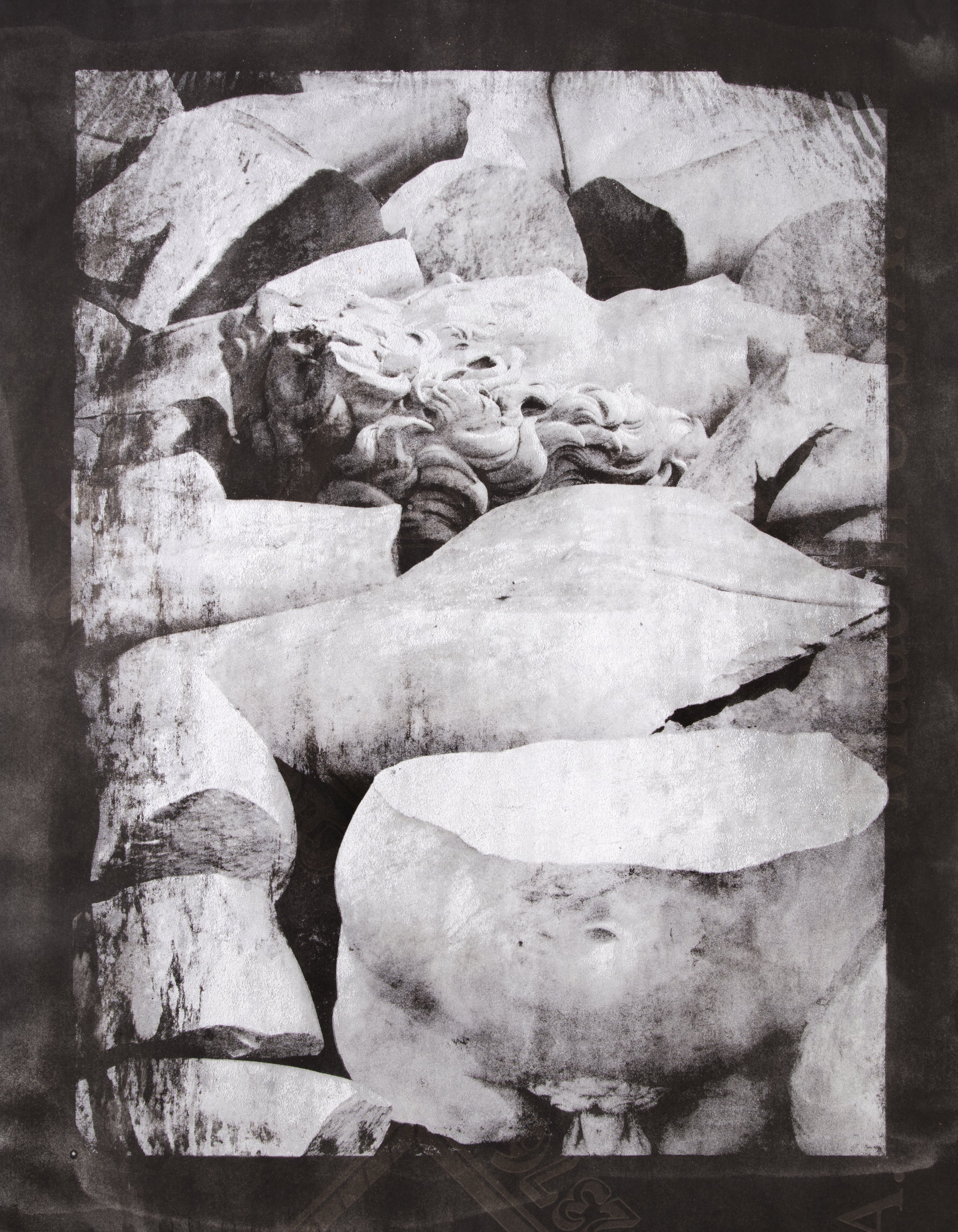

Several of the works on view present as two-dimensional images, engaging sculptural concerns in their conception. To make his photograph David 2F (2020-22), Matthew Brandt captured several images of shattered pieces of a fallen replica of Michelangelo's David–carved, as the original, in Carrara marble–which toppled at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles in 2020. Printed on roofing paper with dust from the fallen statue, the picture is imbued with literal material fragments of a sculptural form. In Barbara Kasten’s long running Construct series, initiated in the early 80s, and Matt Lipps’ Camera (2013), tableaux of overtly sculptural objects and erect images respectively are constructed and arranged solely for the purpose of producing still two dimensional images, which become the final artworks. Both artists embrace strategies of commercial display, including and complicating the display framework as part of the piece. Referencing a history of photographic documentation of sculpture, earthworks, and performance, Rachael Browning’s photograph and related drawing, both titled Ferguson Perforations (2021), operate as a stand-in and facsimile for a sculpture made exclusively in service to creation of these two-dimensional works.

Christopher Richmond’s Trash Moon (2023) documents the fictional formation of a second moon following a Kessler syndrome-like event—a cascading series of collisions by artificial space debris in the Earth’s orbit. As debris collides and sticks together, a small gravity well forms, allowing more and more refuse to consecrate and create the new titular celestial body. Trash Moon combines film, live-action miniature, stop-motion, and CGI to mimic the collage of refuse that combines to form this second moon. At the same time, the audio score employs spatialized audio and psychoacoustic elements to place the viewer inside an immersive counterpoint between the vastness of space and the frenetic, swirling collisions of debris. Together, generations of change compress to minutes, both flattened to a screen that culminates in a dramatic double Solar Eclipse with Trash Moon, the Moon, and the Sun, and elevating crude objects and garbage into illusory sculptural forms.

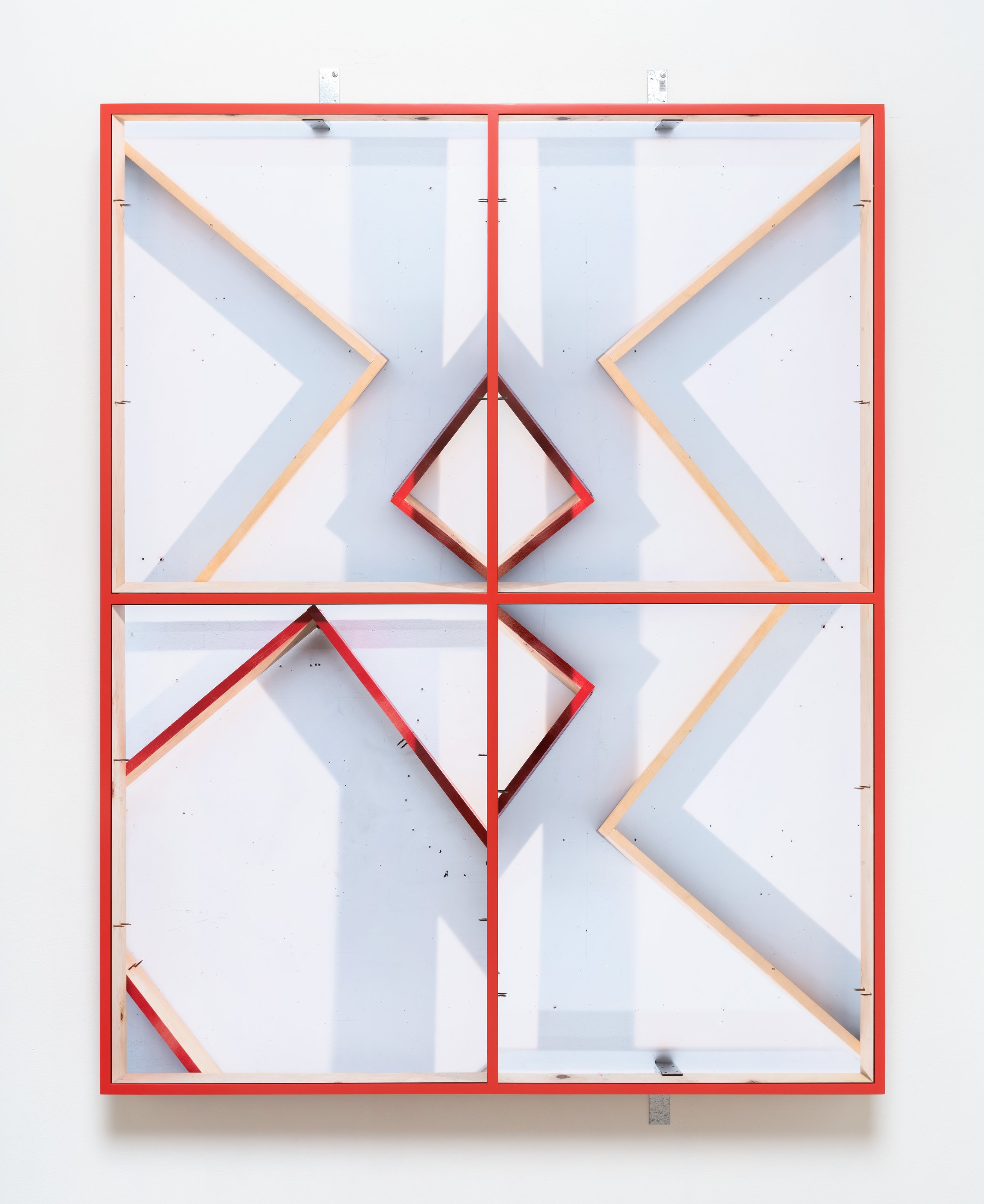

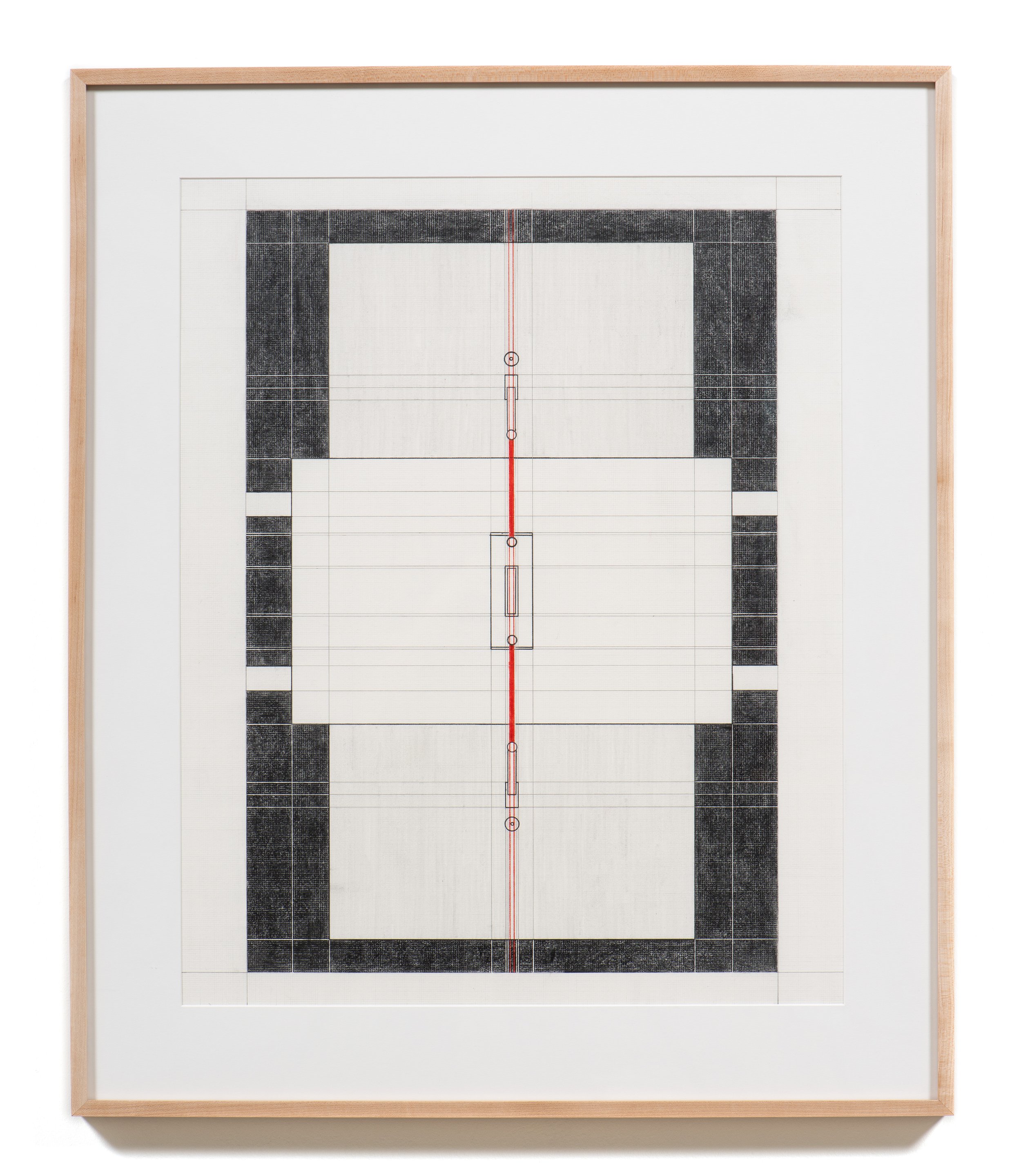

Another series of works play directly with tension between illusionary volume and obvious flatness. Anthony Lepore’s new piece intertwines vernaculars of geometric abstraction and minimalism in a balancing act between physical and photographic line, shadow, depth, and surface, offering a meditation on change and the passage of time. Gregory Kalliche’s Mallard nest (2016) and Spaghetti universe with earth (2016) each presents a UV print on a substrate made by 3M called Controltac™–a product manufactured to allow for graphics to wrap around forms without warp or interruption–adhered to a folding chair, which, alongside the content of the images themselves, echos the consideration of expansion and contraction of material in space. In Joey Frank’s photographs, crushed water bottles float in nebulous void-like spaces, in one instance with a frame mirroring the shape of the bottles it depicts.

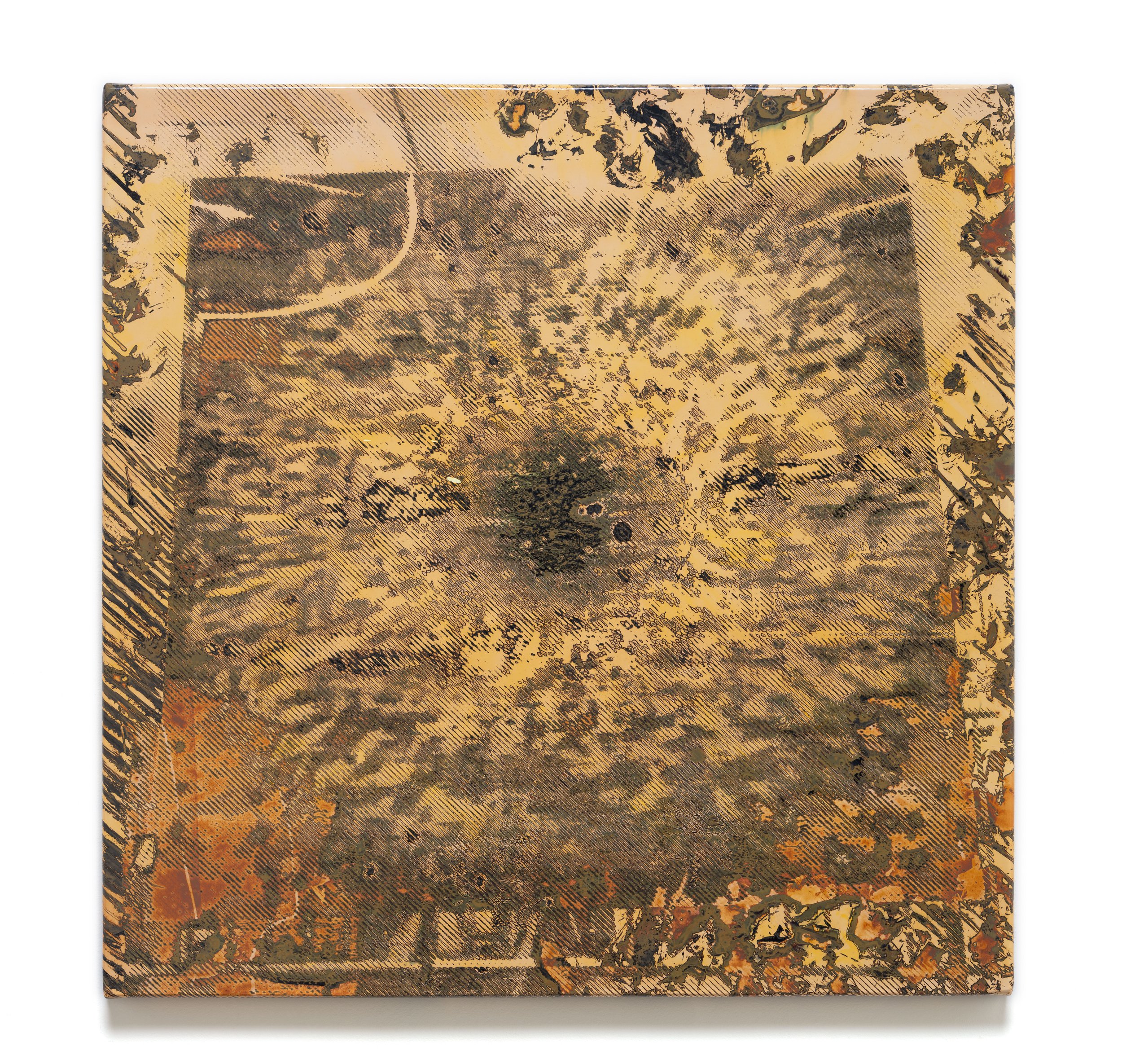

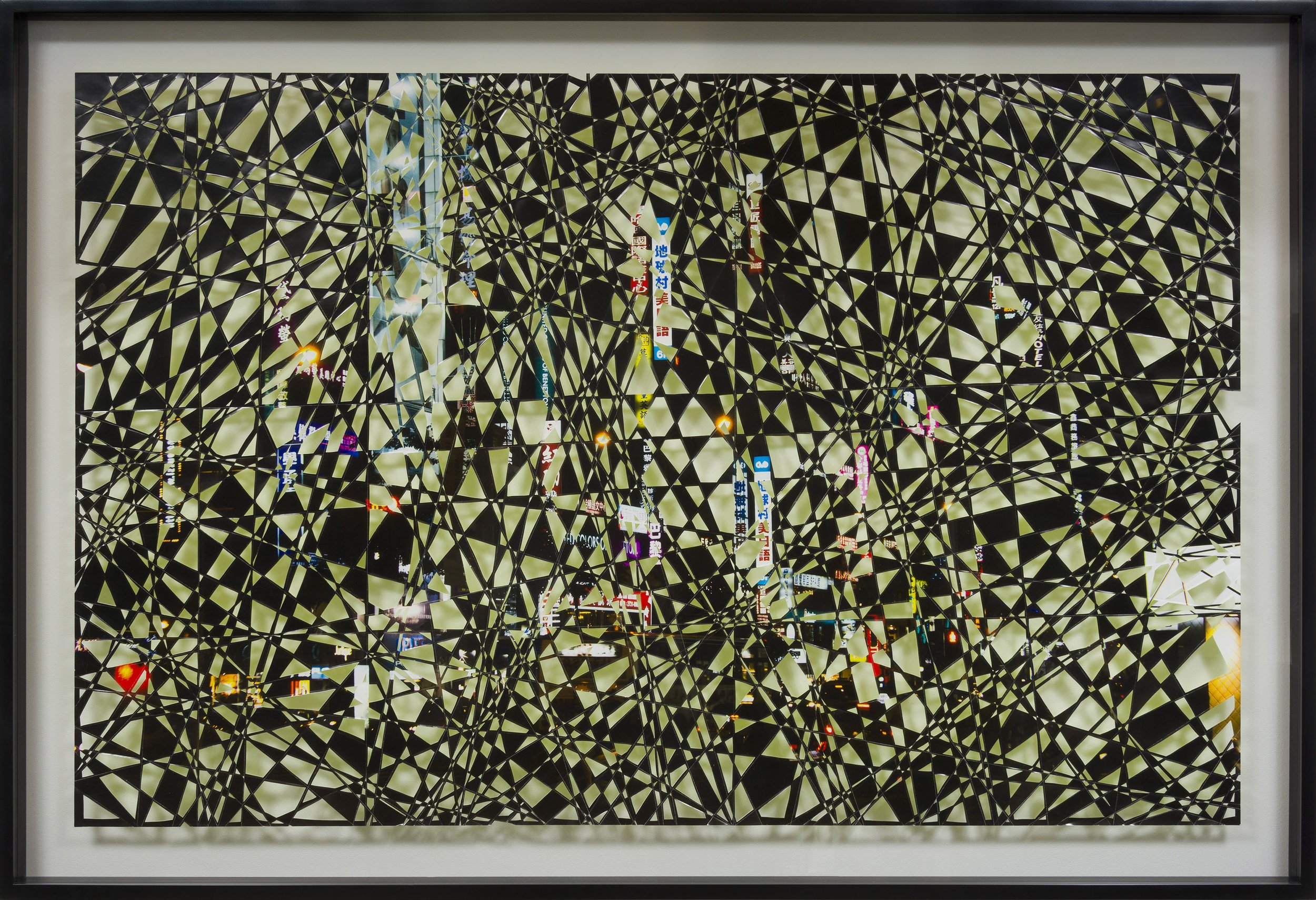

Remaining pieces are concerned with photographic images or techniques fused with material, and the manipulation of this material in space. Both Letha Wilson and Adam Moskowitz utilize UV printing to adorn unorthodox substrates (concrete, aluminum, and steel), producing architectural forms flanked by images that reference both made and organic elements. In Brian Bress’ new video work, an image that at at first appears to be static is slowly and deliberately cut away from behind–the more the image is manipulated, the more it gives way to the nature of the material–it falls, droops, and sways, simultaneously changing the composition and revealing its maker. Valerie Green’s new photographic work initially reads as flat–though upon close inspection, it is revealed to be a series of receding prints cut away to expose ecstatic patterns and forms. In distinctly different approaches to layering and complicating source material, Antonia Kuo uses a series of techniques to create photochemical paintings on light-sensitive paper, while Soo Kim painstakingly cuts away specific information from her images to draw attention and open interpretation of her subject matter.

Text by Nicholas Barlow