Julia Weist

works exhibitions news about

Private Eye

September 14 - October 19, 2024

exhibition text

Julia Weist never expected to become a private investigator. Compared to the cops, fire marshals, and insurance fraud analysts who are normally granted this powerful license, her primary qualification was a 2019 public art contract with the City of New York that embedded her in the Department of Records and Information Services. It was hard to imagine that the bureaucrat reviewing her application would see this period of artistic research as “investigative experience” or the resulting photographic prints—layering city records about the arts with the retrieval slips used to obtain them—as “evidence.” More likely Weist would follow the path of other denied applicants: she would appeal the decision and proceed to adjudication, when a judge would determine how her practice failed to qualify her for the job.

Weist spent several months preparing for this outcome. Her artwork would literally be put on trial, and the record of the proceeding could serve as raw material for a future project. The New York Department of State had other plans for the artist—it approved her application.

Our popular idea of the private investigator comes from film noir: the silhouette on frosted glass, the demons and drink, the cigarette forever on its last drag. This character is often an amateur and almost always a lone agent, nimbler but less resourced than law enforcement. His clients are impatient, and the money is usually good, so any means are the right means to obtain what they’re seeking.

Much like its depiction of the art world, Hollywood hasn’t exactly striven for accuracy. As Weist came to learn firsthand, licensed private investigators cannot operate with impunity, though provided they follow protocol, have extensive access to sensitive and private information. This is the departure point for the work in Private Eye. In adherence to the letter but not the spirit of the law, she has directed the gaze of the private investigator beyond its usual targets—and even back at herself—producing a comedic, elegant, and unsettling portrait of contemporary surveillance.

Throughout the exhibition, Weist exploits loopholes to source visual content from the databases now at her disposal. Inputting the make and model of her car, for instance, yielded the VIN numbers, addresses, previous license plates, and loan and lien information of other Subaru Legacy owners in her town. Searching for license plates with words like “honk” and “believe,” Weist was startled to find such language extending to bumper stickers, lawn signs and even a pedestrian’s sweatshirt. So many details of our lives have been documented without our knowledge, can be privately accessed, and may become part of a story being written about us. Weist’s pieces give us the vantage point of the private investigator, but their effect is to help us realize just how vulnerable we are to capture.

The aforementioned works are pigment prints, showing paper records that Weist carefully arranged to obscure sensitive personal information beneath other layers. While this approach makes a massive surveillance apparatus graspable by the human hand, it also produces material that must be destroyed. Indeed, a paradox for a licensed private investigator is the need to shred data before it leaves the office, and at the same time, keep a paper trail of their professional activity in case of an audit by the state. Alongside the prints, three works of handmade paper test the limits of this logic, created from shredded and pulped records of people with traffic citations, those sharing Weist’s astrological sign, and (in a nod to PI cliché) her spouse. Operating beyond anticipated use cases for the law, they turn paper debris into optical fields teeming with data.

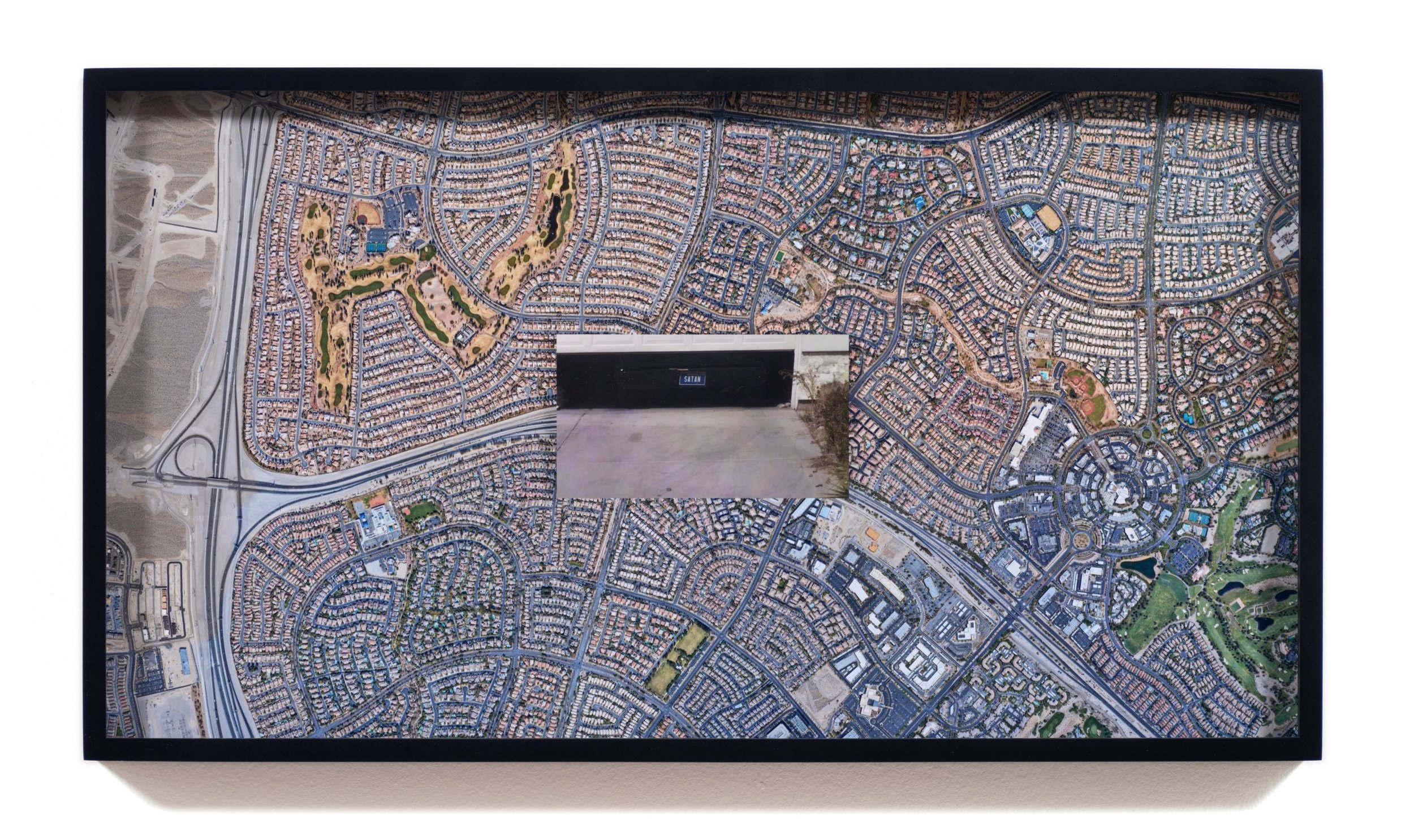

Vehicle Sightings, another series on view, employs a database populated with images shot by tow trucks in search of cars to repossess. Though taking photographs isn’t necessary for this process, as a scan of a license plate will trigger an alert, there’s money to be made in generating photographic ‘proof’ that vehicles have been at specific locations. Seeking to intervene in this visual economy, the artist parked her and friends’ cars near the entrances of repo yards to increase the chance they’d be seen, then searched for their plates on the database to obtain the images on view. What results is true PI cinema, filmed by unwitting repo men and performed by vehicles Weist embellished with flowers, an oversize tutu, and Holbein’s anamorphic skull. To make the companion series Watching the Watcher, Weist ran the plates of the tow trucks themselves, discovering images of trucks accidentally shot by others. Taking a postmodern turn, this particular surveillance network happens to play itself.

Weist, sunburned after hours waiting for her closeup, sits on the curb in one image from Vehicle Sightings. She stares the camera down while meeting our gaze, acknowledging that she too is caught by the system which gives her considerable power over us. Other works on view also double as self-portraits, or better put, portraits of the artist as multihyphenate. Her collage of custom letterheads—with fanciful agency names like “Palette Intelligence” and “Unique Prints”—is unlawful for Weist the private investigator to display, as it includes more than “the name under which the licensee is duly licensed”; however, when Weist the artist hangs it in a gallery, where it can read as a satire of an over-professionalized creative, does the legal risk remain? When Weist the professor designs a union membership card for the Bard College chapter of the AAUP, is she violating numerous rules, dating back to the 1893 Anti-Pinkerton Act, that keep private investigators at a distance from unions?

In the deceptively slightest gesture of the show, Weist exhibits a unique copy of her private investigator license. Printed on a near-match for the original paper and cut with a similar perforating rotary blade, the object dares you to mistake it for the original—down to the void pantograph hiding in plain sight. Its title, excerpting the law, informs that if this license is had, held, or displayed by any person other than the issuee, both parties would be guilty of a misdemeanor. While no language specifies a penalty for having, holding, or displaying its reproduction, it bears stating: caveat emptor. A piece of paper imbued with so much power that only one person is allowed to possess and show it: one could as easily be describing a private investigator license as a singular work of art.

Text by Tyler Coburn

Julia Weist is a visual artist based in New York. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Guggenheim Museum, Brooklyn Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Jewish Museum among other collections. She has recently exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, Art Institute of Chicago, Queens Museum and The Shed and internationally at the Hong-Gah Museum, Taiwan; nGbK, Berlin; Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam and the Gwangju Biennale. Her most recent solo exhibition was at Rachel Uffner Gallery and her latest public artwork, Campaign, debuted in Times Square in 2022. Private Eye is her first solo exhibition in Los Angeles and her first with the gallery Moskowitz Bayse.