Mary Herbert

works exhibitions news about

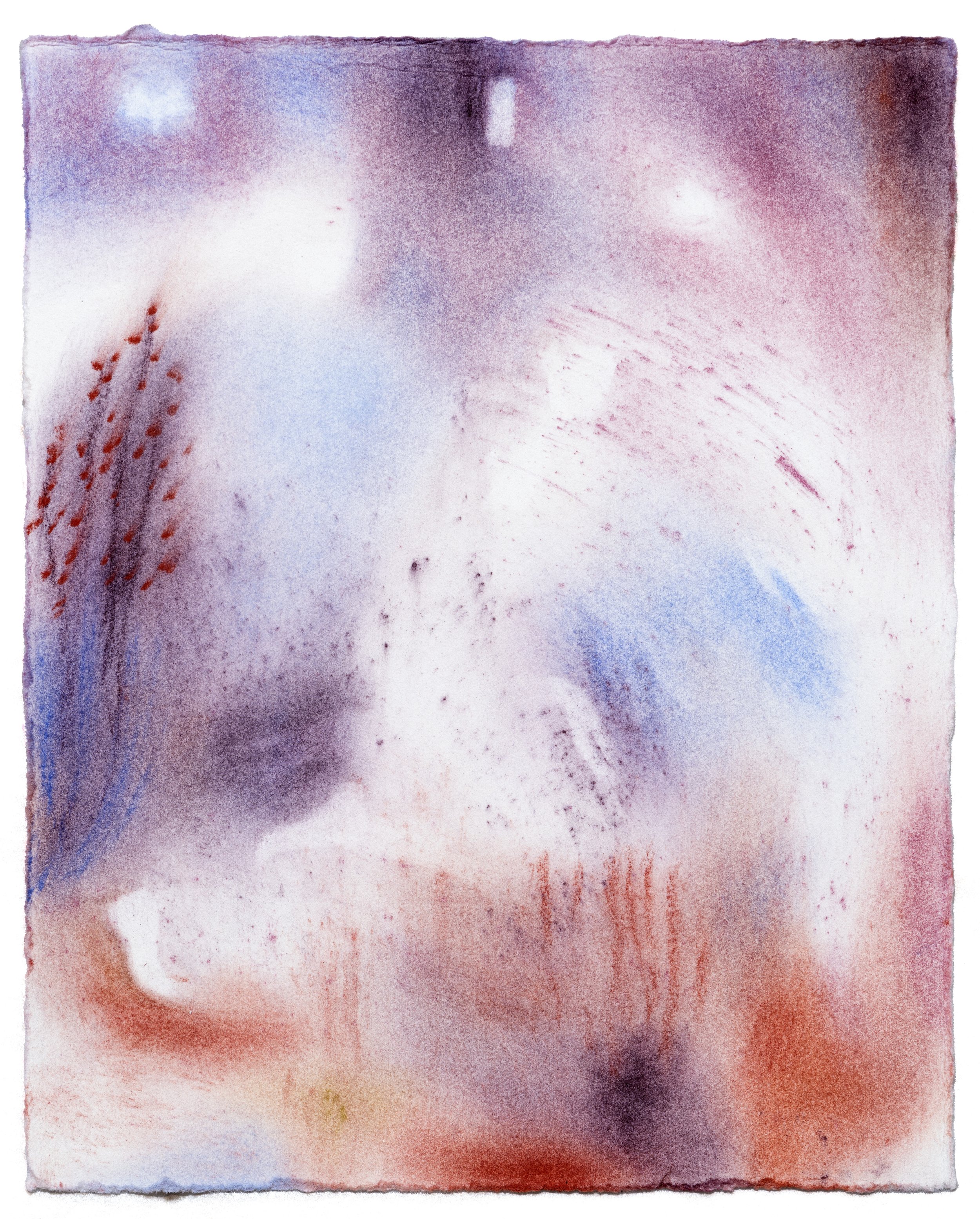

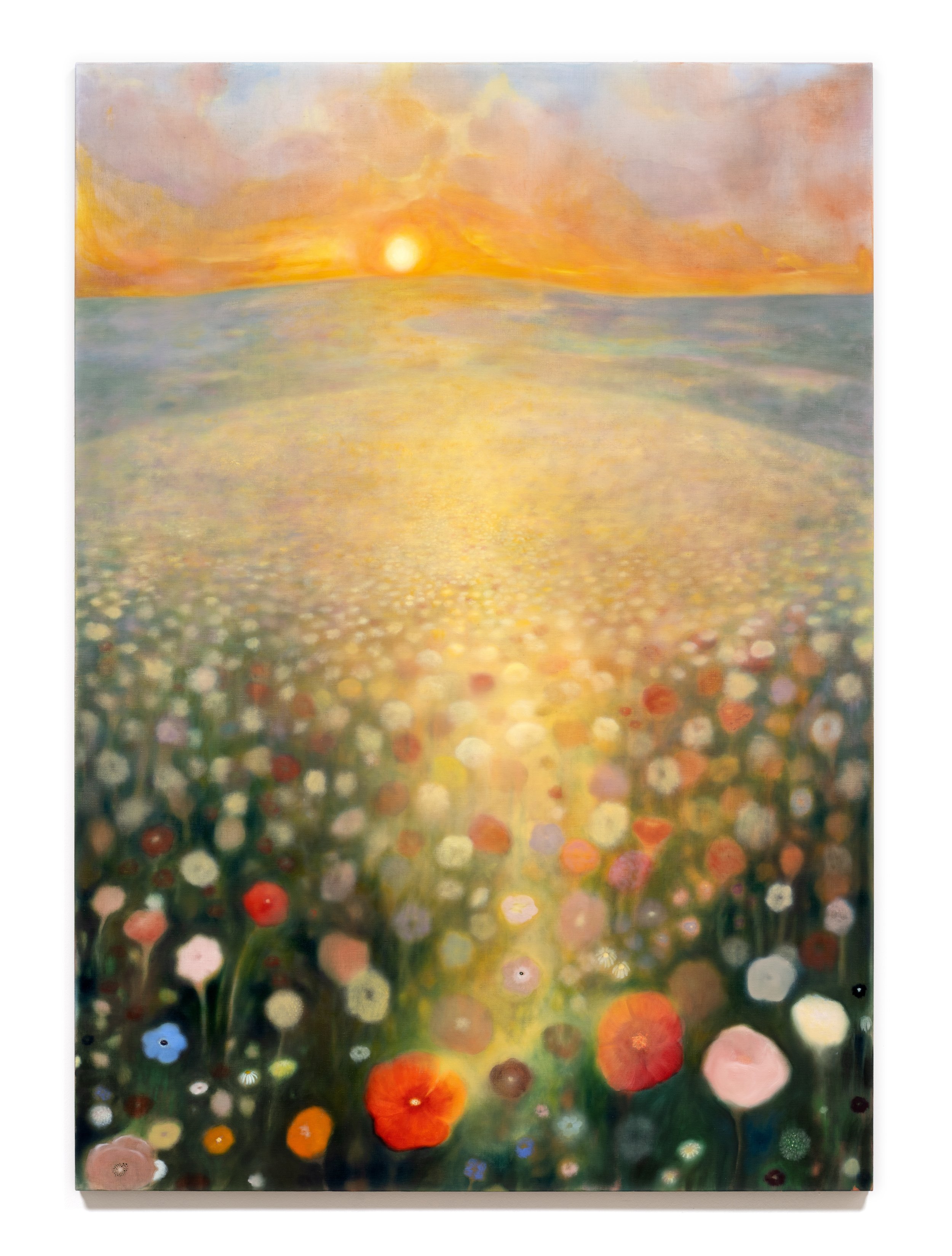

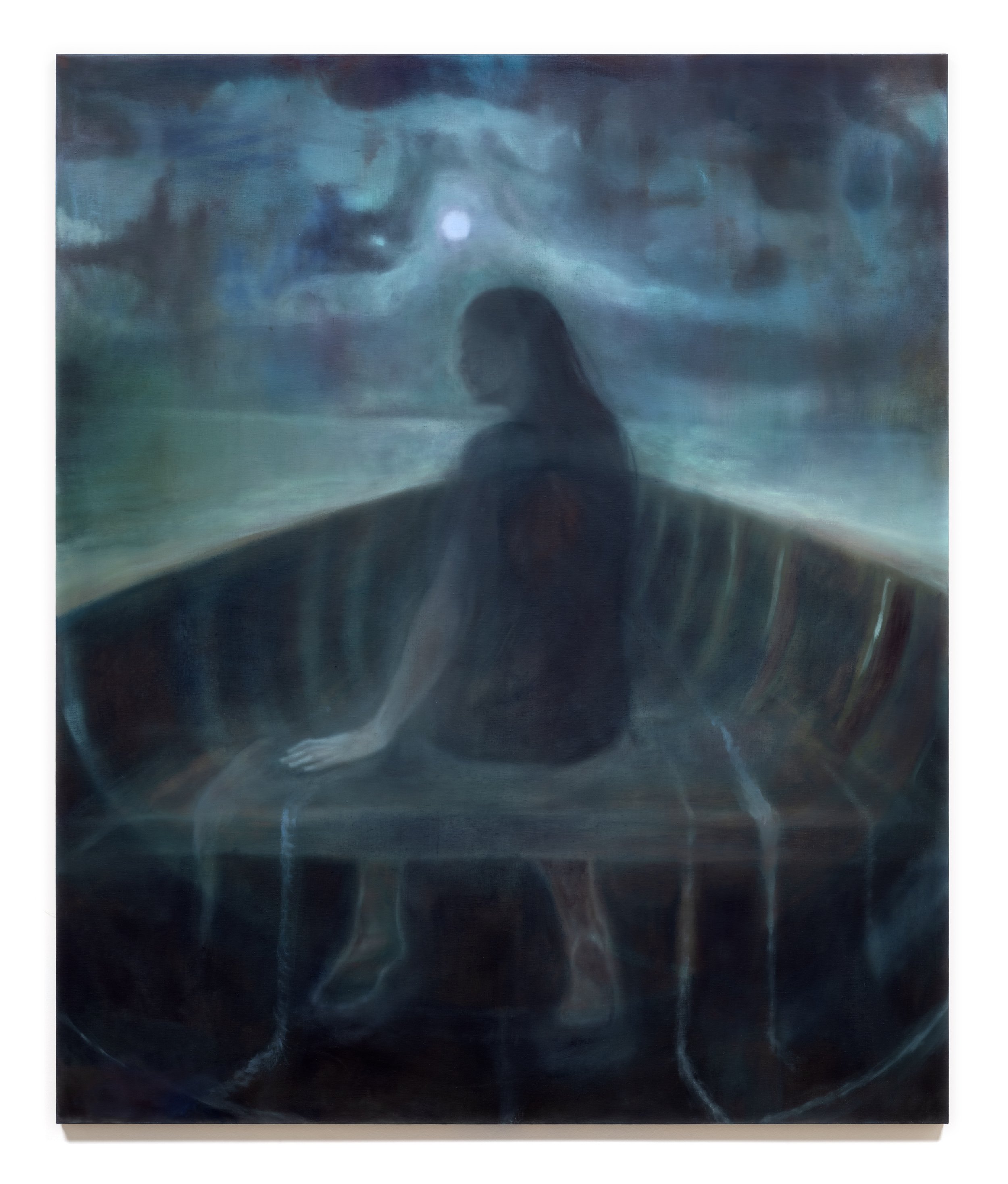

soft logic

September 16 - October 21, 2023

soft logic

Except I shall see in his hands the print of

the nails, and put my finger into the print of

the nails, and thrust my hand into his side,

I will not believe

John 20.25 (KJV)

The Inner – paints the Outer –

The Brush without the Hand –

[...] The Star’s Whole Secret – in the Lake –

Eyes were not meant to know.

Emily Dickinson, c. 1862

A mollusc has something called a mantle, often described as cloak-like, which it uses to form its shell. It does this by taking in minerals from the surrounding sea which it then secretes in thin layers. Over time these layers form a spiral. By expanding, rotating and twisting its body slowly, a shell forms over and around the soft animal. As it grows it builds itself another rotation, and it seals off a spire behind itself. Over time the shell holds oxygen in its earlier rooms, their doors now closed. This scaffolded air allows the creature to float and move.

Just as a mollusc spins itself a shell in layers, these paintings have been made slowly to hold something soft that moves so it can still itself. The method in making something, the soft logic in a spiral form, is that you’ve got to move further from the centre to go anywhere, or you must move closer, further inward. Staying on your one foot, concentric, won’t make anything – to make you must move. When you coil a carpet or roll up a very large piece of paper there is an unruly strength in the middle. It doesn’t want to hold but it does. It keeps the movement of the thing that needs containing, the will of the whole. Something becoming lost, or becoming, can somehow be held in a painting, a still thing.

There is a fresco of a pregnant Madonna by Piero della Francesca called Madonna del Parto, a postcard of which Mary Herbert has pinned up on her studio wall. Parto means ‘childbirth’, but also ‘labour’ or ‘creation’. The painting shows a woman flanked by symmetrical angels who hold open two curtains like the bivalves of a clam shell. She stands in the middle, her dress another curtain over her full belly, closed but for a small gap held open by one hand and by her pregnancy. The hand touches at the middle place where the blue robe parts into white underclothes in a diamond shape. Her fingers are complicated, parted from each other like a squid, something pallid, a clasper, with every digit acting separately. In memory, one finger does the most feeling, but looking again at the painted hand it could just as easily be seen as shielding that part of herself from sight. The hand may really be read as doing both, covering up while also feeling the spot it hides.

Looking at this central hand that worries the parting in the dress makes you feel the sensation of a raw place being touched. As the viewer, you are feeling both as finger and as opening. It recalls the incredulous Saint Thomas and his poking scepticism. The resurrected Jesus tells Thomas to touch his wound to end his doubting. There are lots of paintings that show the saint’s finger caught in the moment it enters the redeemer’s wound. In some, blood slides prettily down one pointed finger, but in others the wound is dry and open as a purse, doubt’s finger halfway in. In Piero’s painting the hand is clean and the white of the cloth remains, the woman’s face serene if a bit exhausted. She is looking slightly downward as though she can’t meet the viewer’s eye, which echoes the demurring hand. She is hiding but also feeling for her own creation, her work, the diamond parting in her clothes which evokes inner mystery as well as, more obviously, sex. She is the doubting Thomas, the sceptic, of herself.

This cloven centre also shapes the periphery in an outward ripple, echoed first in the prismatic pleats of her blue robe and then the waves of the drawn curtains. Even the stonework behind her undulates like a ribbed cockleshell, as though the rhythm and order of what her body makes affects everything. The folds of the white wound cocoon as well as split her. An obvious fertility symbol, the pomegranate, is patterned on the curtain fabric and appears like a row of exclamation marks or cocks graffitied on the cover of a schoolbook, explanatory and doodling. But her body carries true pictorial ambivalence: the split in the composition runs from the centre of where she is most pregnant with meaning, full and divided at the same time.

As successive loops change diameter every time they move around a core, folds of cloth or a snail shell form like language, or like paint, around something vulnerable. There’s the phrase chiral whorls. There are the words meandering asymmetric. There’s iridescent nacre, the secret thing. There is an inherited language of visual metaphors, parts of image-speech invented over time for depicting and talking about invisible and visible things: a human skull, the inside of a cuttle bone, submerged hull of a boat – skull, shell, hull – a husk, little house, pod for a seed, the tension and compression that forms a curve, spiral galaxy, a winding path, hands holding, radial petals, a coiled rope, the whorl of hair on a bowed head.

A painting reminds us that there is a place where language runs out, because it is both excessive and inadequate. This can make us nervous, talking more as we shift about and look, or it can coax us to quietness, unsure of how to say what we think. An intense unsureness can take hold in front of a painting – the desire to look away is suddenly as strong as the desire to keep on looking. In Soft Logic the visibility of each element – each place, figure or object – expresses doubt about feeling and state. This show of question-paintings asks what it means for something to be visible. A universe subdues itself at its own core, a boat is held by the person while it holds them, a flower makes a field which makes a flower. The thing contained is the thing containing; the creature is the shell.

Doubt about the way something and everything form one another is where these paintings place their care which is their meaning. A shell is usually found when it is empty, after the occupant has died or has moved on, but moments of touch hold a thing long after. There are these casings which preserve the artist and clutch the viewer as they scuttle softly and grow old. In one vision, the landscape of the gallery space is a bleached dune on which these shells lie out rotated in bright or artificial sunlight, wondering about themselves as we do. In another, the built darkness of our house is so complete that we don’t know if our eyes are closed or open.

Text by Aisha Farr