impossible apprenticeship

January 6 - February 10, 2024

exhibition text

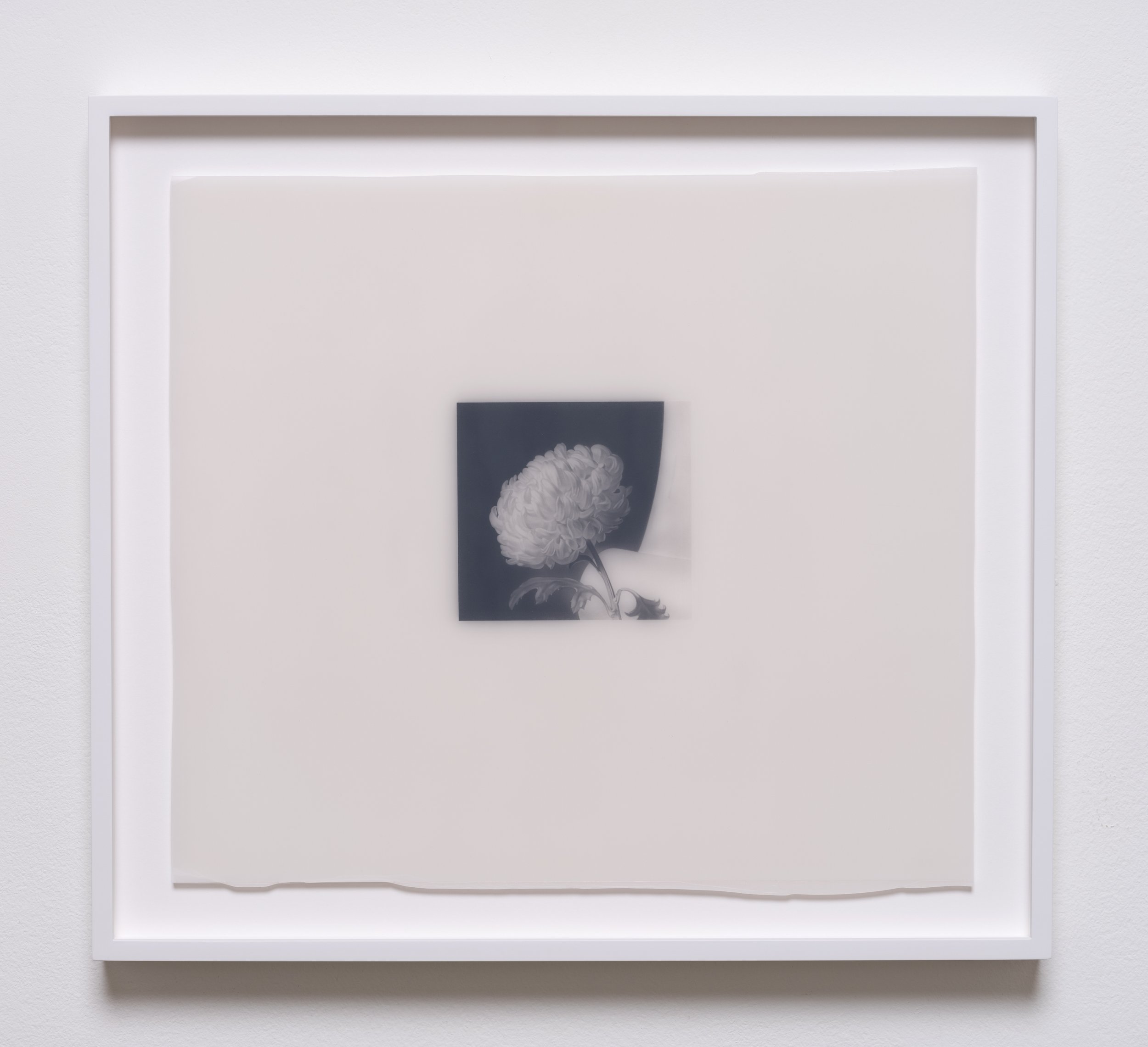

Moskowitz Bayse is pleased to present Impossible Apprenticeship, an exhibition of wax objects and works on paper by Los Angeles-based artist Matthew Gallagher. Opening January 6th, 2024, the exhibition highlights Gallagher's unique and delicate process of melting drafting film drawings onto a body of molten wax, resulting in fragile and ephemeral compositions.

In Gallagher’s homage to the Spanish master Francisco de Zurbarán, FdZ.1630.800.2022 (2022), the artist carefully retraces Zurbarán’s teacup from the masterwork “A Cup of Water and a Rose” (1630). Light travels through the liquid in a porcelain cup, skates across the surface of a pewter plate, and is gently slowed by a rose petal. Gallagher’s wax medium amplifies Zurbarán’s quiet symphony of subtle reflection and translucence as light penetrates into the diffuse surface, forming a halo around the image.

“I am committed to resolving each work no matter how many restarts are needed,” says Gallagher. The systematic nature of the work’s title—artist initials, year of source work, hours spent drawing, date of wax pour—contrasts with the artist’s seemingly irrational procedure. A full 800 hours of drawing are concentrated into the 5.6-by-7 inch composition. “There is an absurdity to the process that makes the successes euphoric and mystifying.”

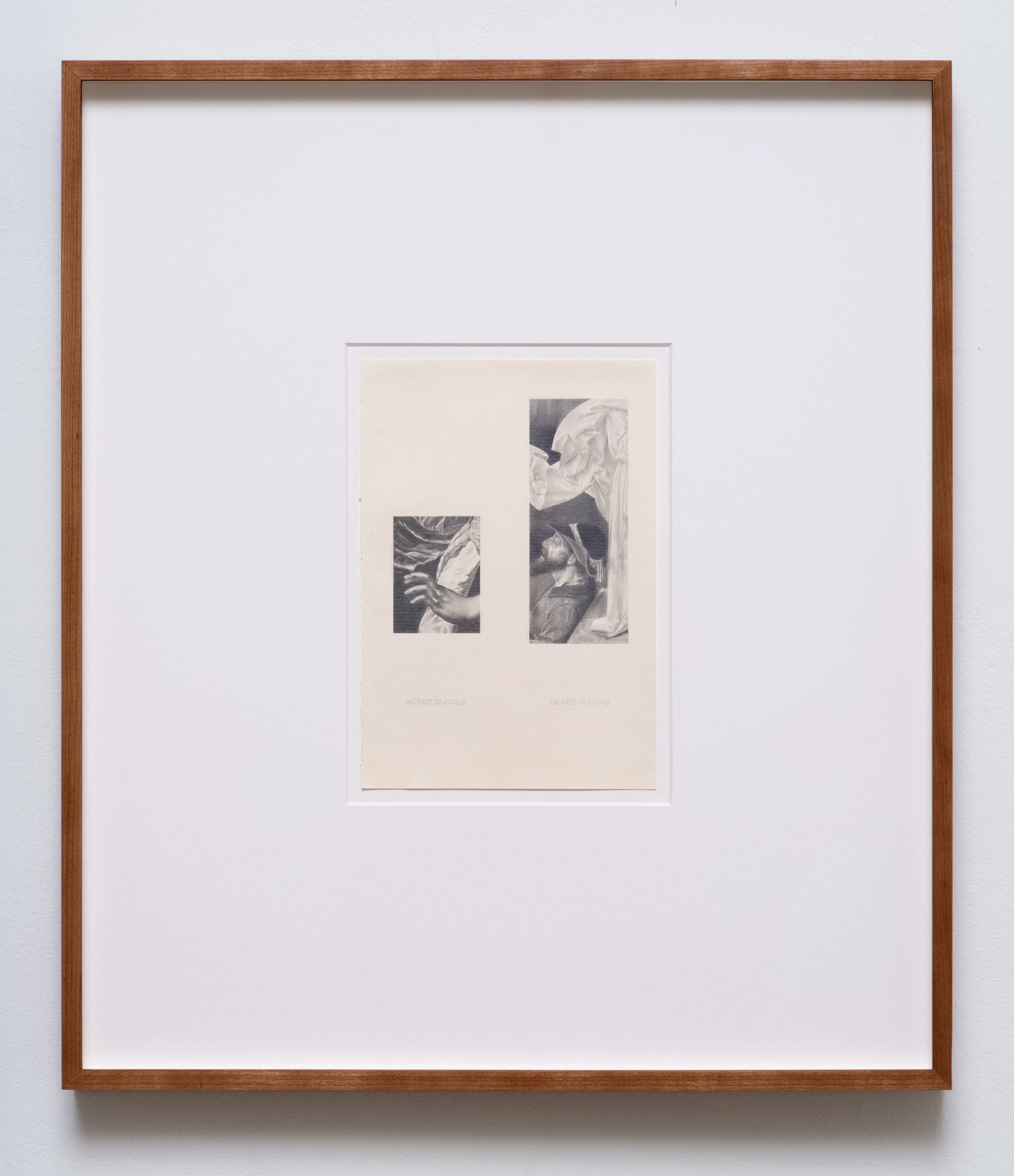

In virtually every other culture and time period, art was obviously, self-evidently, and inherently magical. Cave paintings seeded luck for successful hunts, fertility figures blessed people with offspring, totems pleaded with the natural world, religious icons honored great creators. To the contemporary viewer, critic, and even artist, the spiritual dimensions of art can easily escape notice.

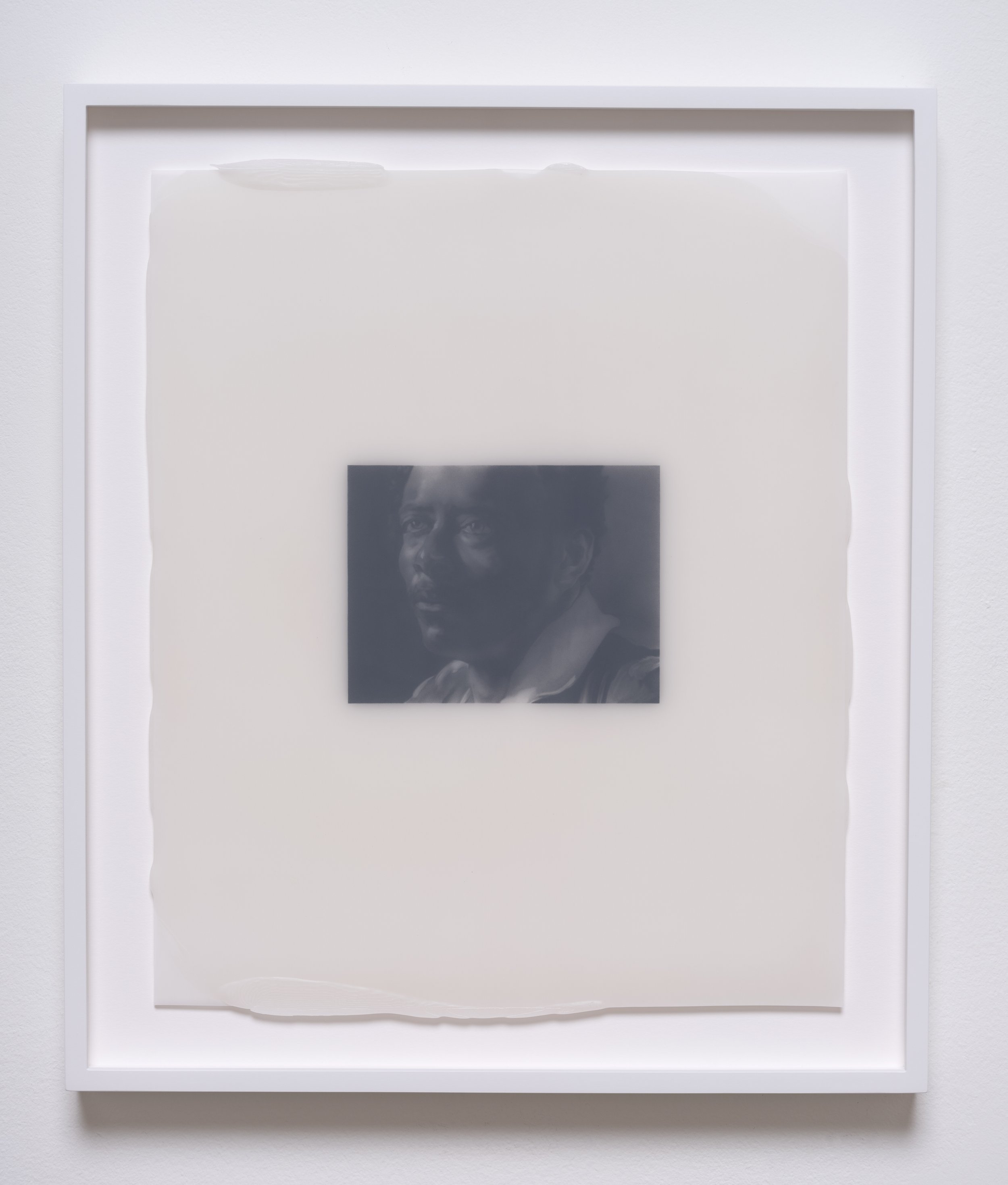

Gallagher’s process is palpably ritualistic. The careful replication of strokes, movements, and imagery is, in some ways, an attempt to commune with the past. The goal is not to create a semblance of the source image, but rather to reenact its creation. “If a line was made quickly, I should draw it quickly as well,” Gallagher notes. The resultant works are wistful and mnemonic, as the artist ventures an impossible apprenticeship with a bygone artist.

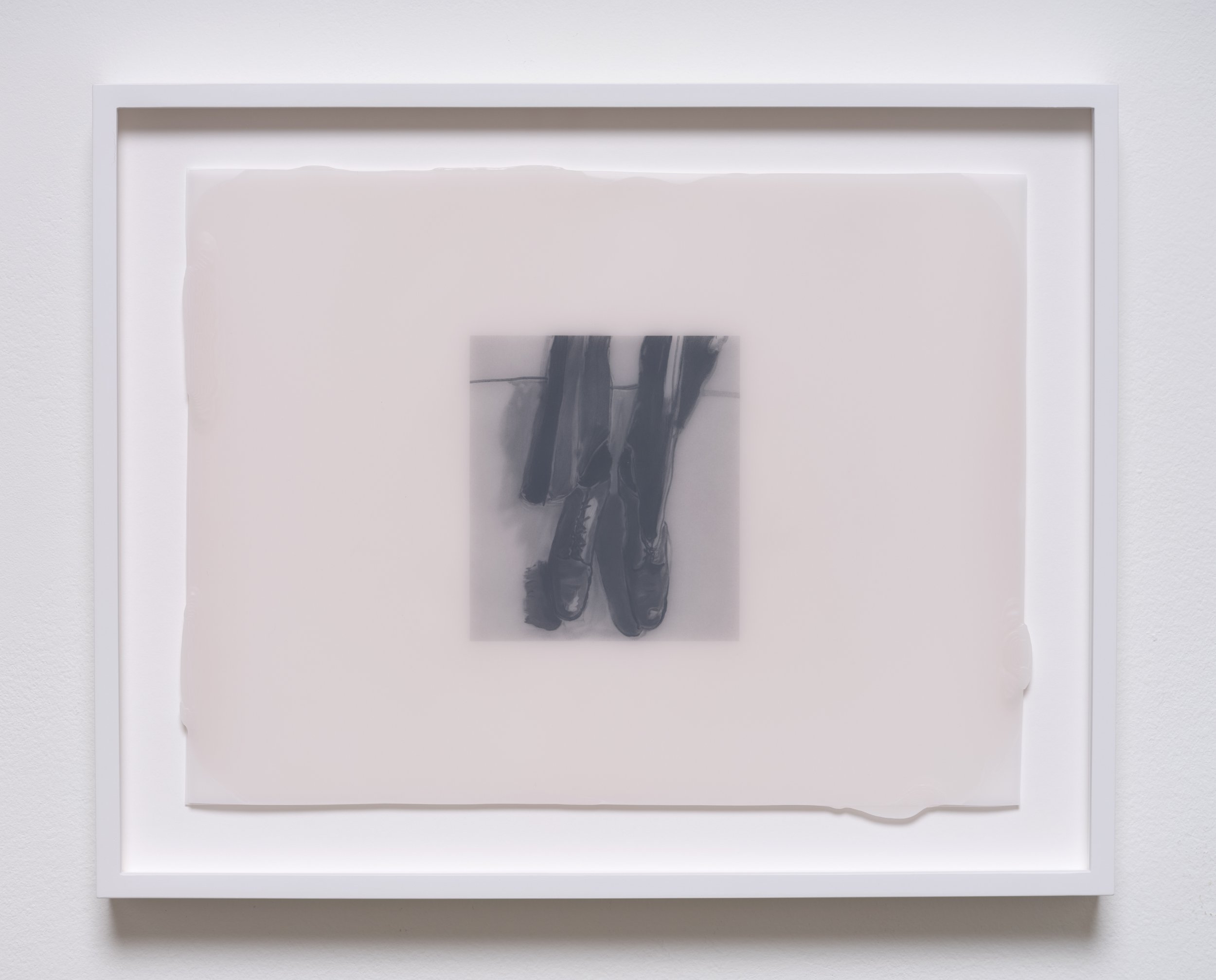

While some of Gallagher’s source material is chosen out of direct admiration, some is chosen recursively—because an artist he admires, admires it. In AN.1970.46.2023 (2023), Gallagher reproduces an excerpt of Alice Neel’s 1970 painting of Andy Warhol—an artist looking at an artist. Warhol’s vulnerable feet dangle from his chair. “It took many, many false starts before a Neel rhythm set in,” says Gallagher. The final precarious transfer to a wax ground often prompts the artist to restart, ensuring the repetition needed for the subtle qualities of the original work to embed themselves deep in his head and hand.

The charm of a handmade work is not a result of its imperfection. The humane energy that radiates from a handmade object is, in some ways, a product of the risk inherent to each phase of its creation. Each move of the hand alters the course of the final work in subtle, lifelike ways. As for anything living, a fatal mistake is always possible at this stage. In Gallagher’s work, each drawing is a product of meticulous observation and hours of dedication. The drawing is transubstantiated in its final perilous transfer onto a wax ground. This process, fraught with the possibility of destroying sometimes months of work, imbues each piece with a palpable fragility.

Gallagher’s six wax objects and three works on paper have a quiet radiance. The works assert that the act of replication can be a ritualistic practice of devotion: one of communing with the past.

Text by Darragh McNicholas