Anthony Lepore

works exhibitions news about

no condition is permanent

February 15 - March 29, 2025

Opening Reception | February 15, 5-8pm

exhibition text

Nodding to the exhibition title, No Condition is Permanent—inspired by and borrowed from a 1970s song by Celestine Ukwu—the conditions are as follows: Anthony Lepore lives and works in a mixed residential and industrial corridor in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Lincoln Heights. His studio is constructed in the middle of a former bikini factory established by his paternal grandfather in 1972. The factory is not only the location of his studio, but often the subject of his work. It is his muse. But lately other ideas and experiences increasingly inflect his art, to name a few: caring for ailing grandparents; spearheading, alongside his neighbors and spouse, a grass-roots coalition for environmental justice for their toxin-poisoned neighborhood; a collection of 19th century portrait photography from one California studio; and formative childhood experiences.

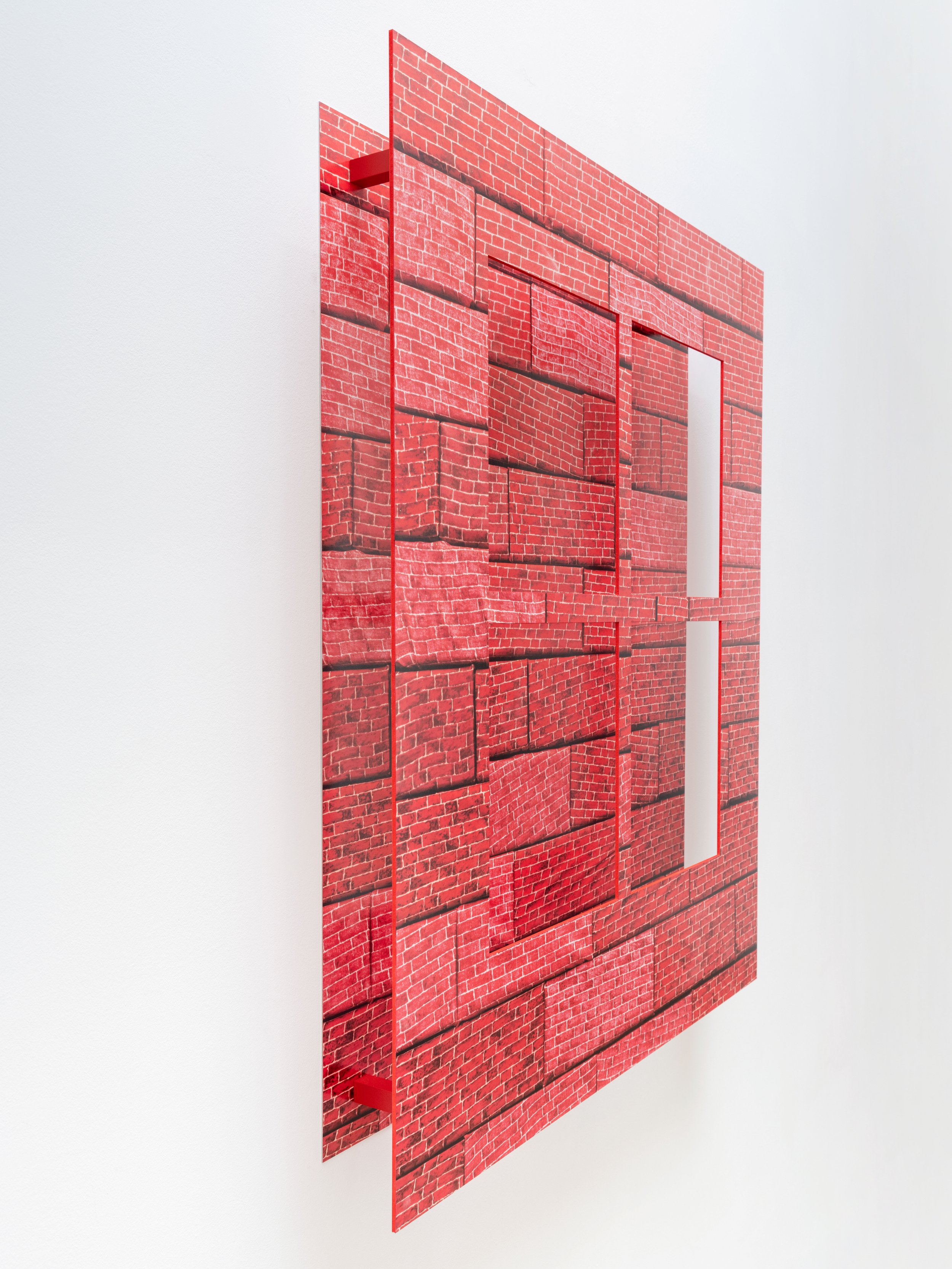

Lepore’s work traffics in the simultaneity of past and present, which plays through his work as fabricated seamlessness between the real and the photographic. As such, his photo-objects and object-photos typically utilize illusions and camera “tricks.” He runs his ideas through photography and processing techniques such as multiple or lengthy exposures, rephotography, and montage. The illusions he generates are sometimes witty (cloud-printed fabric wadded to mimic clouds, paper airplanes, brick/ed windows with views of brick walls), sometimes symbolic (favorite handmade ceramic dishes, ladders), and most often both (magic boxes, pennant streamer shadow play). Lepore’s studio-specific set-ups draw near to audience-of-one performances, sculpture making, process documentation, and stagecraft.

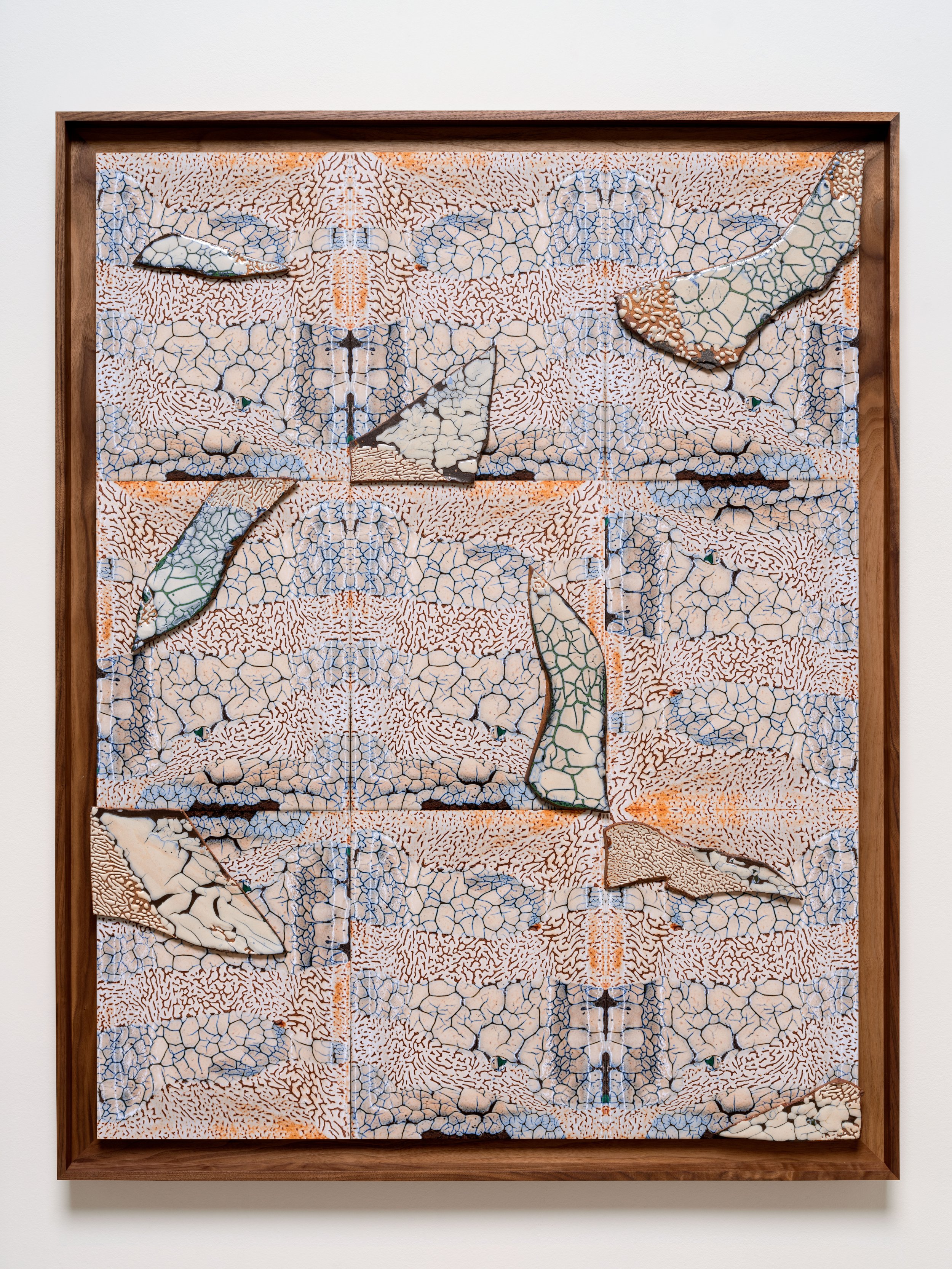

Lepore’s photographs are a means to point to ideas and sensations he wishes to fix in balance: loss/repair, transparency/opacity, material/immaterial, youth/aging, past/present. He infuses his work with a kind of a poetics of the quotidian, a lexicon of everydayness. Beloved cracked plates are immortalized as All The King’s Horses, All The King’s Men and One Into Another, part of a body of work that marries Lepore’s adoration of clay to the camera. Here Lepore underscores process as intrinsic to both his photography and his ceramics: both emerge transformed from an enclosed interior, the camera or the kiln. This is the location where the work develops. In Specter a photo of a ceramic shard serves as support for two attached shards, the composition enacting contingent repair.

Lepore’s body of work points to the conceptual convolutions of representing three dimensional objects in a two-dimensional medium. But his play actualizes both two and three dimensions—one is not swapped for another. His is a practice of legerdemain, a delightfully precise portmanteau that translates as “light of hand” (another coinage for sleight of hand). Light of hand is central to many of his works, but especially in No Condition is Permanent and Tomorrow is Uncertain, walnut box sculptures the interiors of which are visible through a peephole. The boxes adapt a stage illusion popularized in the latter half of the 19th century nicknamed Pepper’s Ghost. The technique manufactures ghostly apparitions with glass and light, a deception you may know firsthand if you’ve ever visited Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion. Lepore first explored Pepper’s Ghost for a fourth-grade science project. Here he condenses and boxes it to focus the eye on a glazed ceramic tile that transforms before our one eye.

While artifice is a key to Lepore’s work, so is the reality of objects, as in the everyday experience of objects in relation to bodies, and what these relations symbolize and convey. In The Way Out a ceramic ladder is affixed to a photo of a steel ladder that was temporarily relocated from an emergency exit in the factory to the studio for its portrait. Both ladders ascend to approximately nowhere. This, and most all of Lepore’s work, is presented at 1:1 scale, a compelling paradox given his illusionary tactics. What you see is what you see—sort of. A multiple-exposure of a round dish evokes an animation of a falling, or failing, object enlivened by affixed small ceramic ovals in Summoning Suns. Community Action captures dozens of white paper airplanes layered and tacked to a yellow-painted surface. Like so many specimens pinned in place, the papers speak to childhood pastimes as much as message relay. The print itself is cut and folded back on itself, an internal duplication and an ersatz flutter.

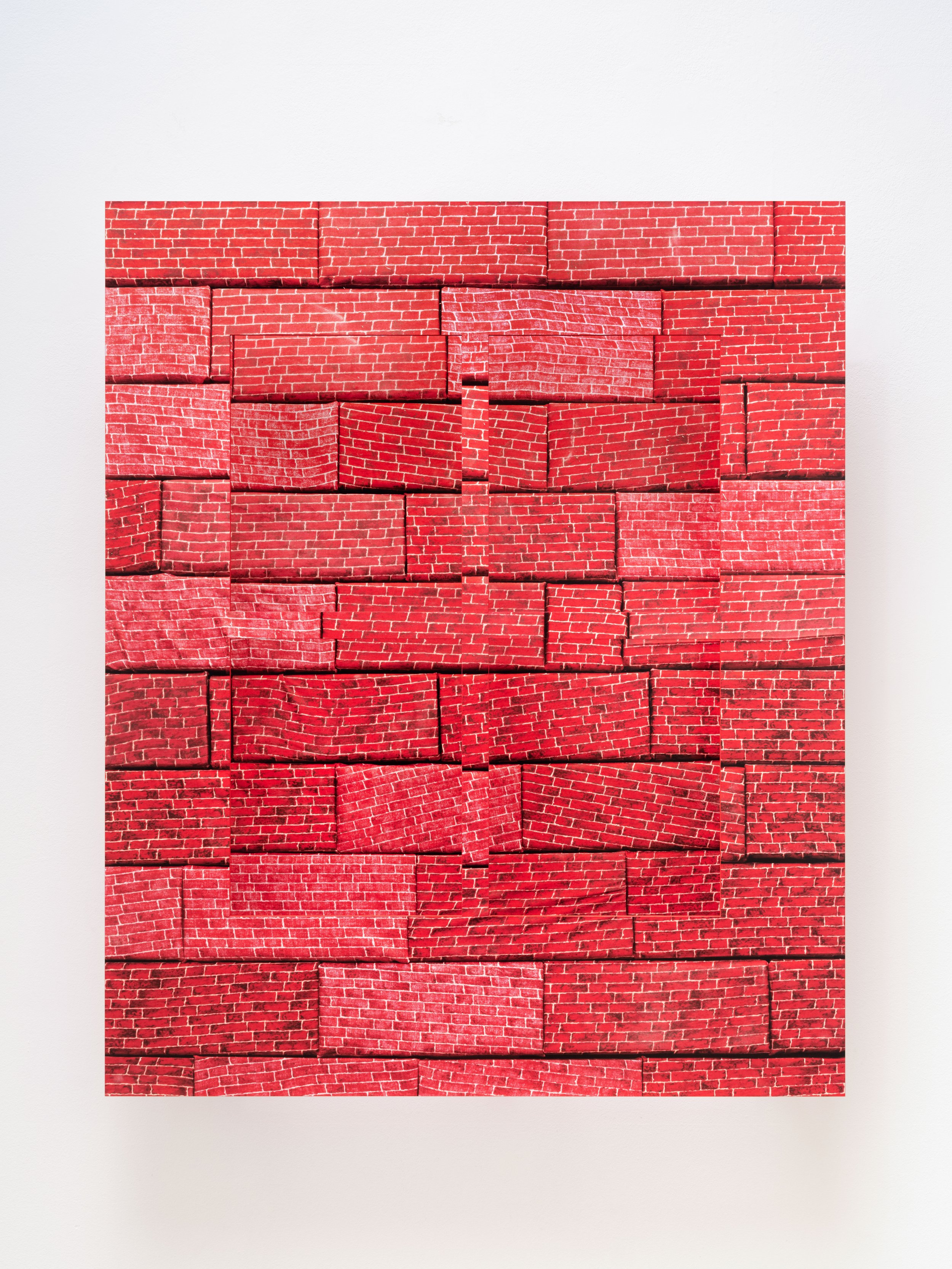

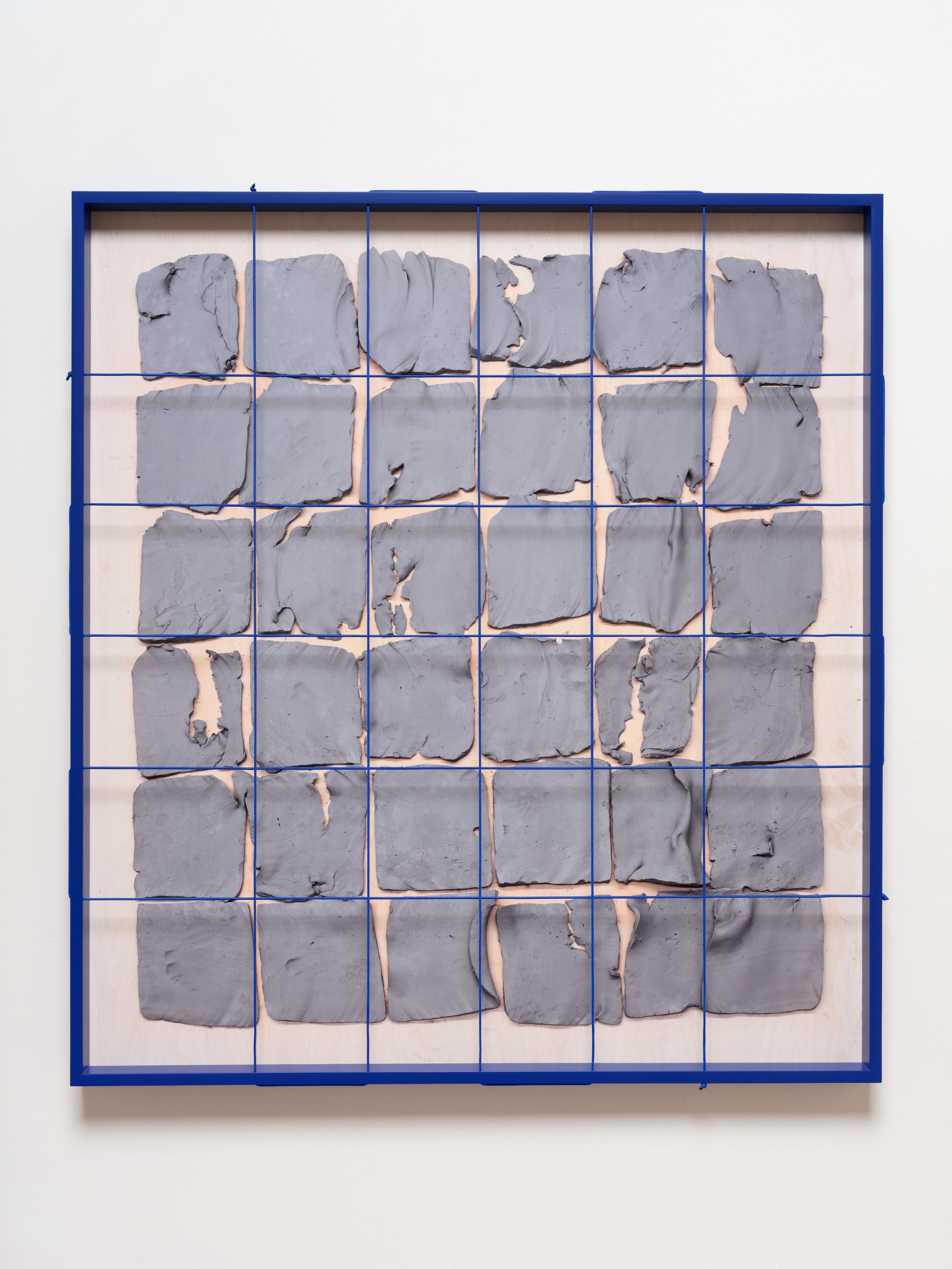

Man Proposes, Time Disposes is a grid of slabs of unfired gray clay, arranged six by six on a cream-colored surface. They look to have been roughly sliced from a hunk of gray clay, slapped down onto a surface like so much deli meat, and documented before sliding off frame. Lepore squares his intention to make a grid photo with the addition of one length of blue string woven through the frame resulting in a string frame for each slab. Another kind of grid characterizes The Long View made with brick-printed fabric wrapped around cut wood. He fabricates a minor melodrama: the brick window gives way to a brick wall. As in a Wile E. Coyote and Roadrunner cartoon, it’s a tragic farce. But the brick (and the brick wall) is also a multipurpose symbol, used in various ways by artists ranging from Martin Wong to Charline von Heyl to Pink Floyd. The brick pattern underscores Lepore’s process of making and remaking, presenting and representing, creating and recreating.

Text by Jenelle Porter

download pdf

Anthony Lepore (b. 1977, Burbank, CA) received his BFA from Fordham University in 2000 and his MFA from Yale University in 2005. His works have been the subject of exhibitions internationally, and are held in the permanent collections of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim Museum (New York), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Hammer Museum (Los Angeles), the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles), the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art (Kansas City, Missouri) and Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven, Connecticut), among others.